Lately I’ve showcased a number of scientific papers that I’ve dubbed “Cool Science”; today is no exception, except this paper is cool for what should be all the wrong reasons. But let me start at the beginning.

In 2003, a group of researchers from around the world (lead by University of Guelph biologist Paul Hebert), published a paper postulating that almost all animal species on the planet could be identified quickly and easily using a short string of DNA (658 base pairs to be exact) and a large database for comparison. This new technique was called DNA Barcoding, and has seen wide coverage in the media and scientific literature over the past 8 years, and who’s proponents have greatly alienated so-called “traditional” taxonomists due to some grandiose claims.

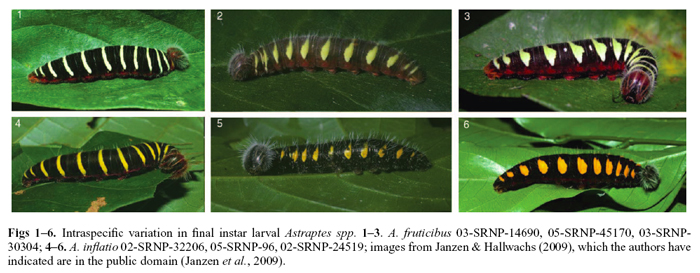

Cut to 2004 when Hebert and famed tropical ecologist Dan Janzen (among others) presented their findings that DNA Barcoding had identified 10 new “species”, which had previously been thought to be but a single species (Astraptes fulgerator, a skipper butterfly – Hesperiidae – from Costa Rica). Normally when a taxonomist discovers a new species, they formally describe it, giving it a species name, providing identifying characteristics, and selecting a single specimen as the holotype (the flag-bearer for that species name, new specimens can be compared to the holotype to judge whether they should be considered the same species or something new). But Hebert et al. didn’t. They considered these 10 new “species” real (pg. 14816 – “Should the 10 species of A. fulgerator identified in this study be formally described despite their morphological similarity? Yes.”), but didn’t do anything about it. No names and no holotypes. This left 10 nameless “species” floating in the wind so to speak, and created 10 taxa which could only be referred to as ad hoc numbers by authors citing this paper (and lots of people cited this paper).

In taxonomy, species which have been incorrectly “named” (those which are not acceptable to the governing body of such things, the ICZN, based on a long list of conditions which must be met) are deemed nomina nuda, literally “naked names”, for they have no definition, and are untestable hypotheses. Think of it like the word “glajensd”: I can use it in a sentence all I want, but without providing a definition for the word, no one will know what I’m talking about, or be able to find it in a dictionary. You can see why this creates a problem for anybody interested in speaking the language of biology!

So these “species” were abandoned, orphaned into the limbo of taxonomy and nomenclature. Until now.

Last month, a paper was published in Systematics and Biology by Andrew Brower in which he cleaned up these nomina nuda and properly described each of the 10 “species” identified by Hebert et al. Well, perhaps “properly described” isn’t the correct term either. Although his work meets all of the standards set forward by the ICZN, Brower himself acknowledges he’s set a bad precedent.

You see, he’s described these species solely on the DNA Barcodes and information provided by Hebert et al. 2004. In fact, he’s never even laid eyes on these butterflies, alive or dead, other than the photos associated with each specimen in the Barcode of Life Database. Here’s a snippet for the description of one new species:

Astraptes boreas holotype - 95-SRNP-8046 - courtesy of BOLD Systems (Creative Commons non-commercial license)

Astraptes boreas sp. nov.

Type locality. Costa Rica, Alajuela Prov. Area de Conservacion Guanacaste, Sector Santa Rosa, Sendero Natural, 10.836° N, 85.613° W, 290 m.

Diagnosis. The species may be differentiated from other members of the Astraptes fulgerator complex by the following combination of character states of the DNA barcode: 52T; 202A.

Holotype. Voucher 95-SRNP-8046, deposited at the University of Pennsylvania.

Note: This species corresponds to the OTU ‘BYTTNER’ of Hebert et al. (2004).

Etymology. The name boreas, a masculine noun in apposition, is the personification of ‘the North Wind’. The species name alludes to the enthusiastic advocacy of DNA barcoding by Paul Hebert and his Canadian colleagues.

You can see all the specimen data that Brower used to describe the species here (click on any of the “Specimen Page” links to see full data).

So what if you wanted to identify the butterfly you caught while on vacation? Well, there are no identification keys, and you can’t relate back to a physical description, meaning the only method of identification is to DNA barcode your specimen, a technique not readily available to the public (or many researchers without specific funding). Anyone else see the problem with this? From a taxonomist’s point of view, this is just the tip of the iceberg, as there are several more serious concerns on how these new descriptions will relate back to previous work (I won’t delve into it here, but Brower provides a succinct discussion of these concerns in his paper).

Clearly Brower doesn’t condone this approach to taxonomy, and is using these species as an argument against claims that DNA Barcoding is the cure for the “taxonomic impediment”:

If publication of these names and associated diagnoses provokes an outcry, so much the better for science. On the other hand, I would be dismayed if it established a precedent for similar technically correct but empirically vacuous barcode-based species descriptions. Perhaps the most ‘serious’ point of these descriptions is that simply because species can be identified and publicized on the basis of a few nucleotide differences it does not mean that they should be. (Brower 2010; pg. 488)

As a junior researcher following the “traditional”, whole-organism & total evidence approach to taxonomy, I applaud Brower’s work in this paper, and hope that it draws the attention of the entire taxonomic community, invigorating further debate into the use of DNA Barcoding for anything besides specimen identification. (I just hope I’m not shooting my career in the foot for backing it…)

What do you think of these new species? Drop a comment with your thoughts!

References:

Hebert, P. D. N., A. Cywinska, S. L. Ball and J. R. deWaard (2003). “Biological identifications through DNA barcodes.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 270: 313-321.

Hebert, P. D. N., E. H. Penton, J. M. Burns, D. H. Janzen and W. Hallwachs (2004). “Ten species in one: DNA barcoding reveals cryptic species in the neotropical skipper butterfly Astraptes fulgerator.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101(41): 14812-14817.

Brower, A. V. Z. (2010). “Alleviating the taxonomic impediment of DNA barcoding and setting a bad precedent: names for ten species of ‘Astraptes fulgerator’ (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae: Eudaminae) with DNA-based diagnoses.” Systematics and Biodiversity 8(4): 485 – 491. (This paper is not open access, so if you’re not affiliated with an institute which has access, contact me)

I look forward to reading the actual article, it does boggle my mind a little that anyone would do this even if it was just to stir up a hornet’s nest. I guess best case scenario this might push the ICZN to change. However I think it is more likely we will see a sudden influx of amateur species descriptions based only on COI. Booooo.

I’m not sure how the ICZN could prevent this sort of thing, and at the speed that ‘code’ updates happen, a lot more bad taxonomy could occur.

There are lots of stuff to be said about Hebert et al. (2004)’s paper; the best criticism of which can be found in Brower (2006: 10.1017/S147720000500191X). Despite most accounts, the 10 species are not in fact based solely on barcodes, but on a combination of feeding ecology, larval coloration and cox1 partial sequences. What provoked me the most was, however, that no formal naming took place.

Hebert et al. designated their species codes like “SENNOV” and “INGCUP”. Philosophically, there is no major difference between these and Linnaean names – both are proposed hypotheses about the affinities of a group of organisms, and both can be refuted, changed or strengthened given good enough evidence. The practical difference is that Linnaean names represent the dominating nomenclature system in biodiversity science, and that they are governed by a set of widely accepted rules (the ICZN).

What Brower is doing now is the right thing to do, even though the taxonomy is not necessarily good. When some butterfly taxonomist in the future reexamines Astraptes using both DNA and morphology, undoubtedly some of these names will be synonymized with each other and with A. fulgerator and A. catemacoensis. Ideally Hebert et al. should have done this – proposing their hypotheses about species status in the same language that other biodiversity scientists are using to propose species hypotheses.

I fully agree with you Gunnar. Half-baked taxonomy doesn’t help anyone!

Its weird because our lab just had a meeting about a manuscript that a certain PhD student co-supervises in Guelph wrote on DNA Barcoding of gall wasps. Let’s just say we weren’t pleased… I would still use DNA Barcoding as an aid for my taxonomic work, and no doubt in my manuscript I would reference Hebert et al. 2003…but in the end unless I can back that up with morphological/biological characteristics I would not so hastily publish my results…

Very interesting find Morgs, thanks again for keeping us informed1

As Chris mentioned, I hope that this paper doesn’t give people the impression that COI species descriptions are A-OK now, which could arguably be the single worst thing to happen to the science of taxonomy. Ignoring the bigger picture never ends well….

If/when that paper you previewed gets published, I hope you’ll send it along!

I haven’t seen the Hebert and Janzen paper, but if no names were applied to the “new species” then no nomina nuda were created. I actually believe that was a more responsible approach than that of Brower, although I understand the motive behind it.

This is where it gets fuzzy I think Ted, as the authors of Hebert et al 2004 explicitly refer to several genotypes as species and provide a 4-6 character identifying “name” for referencing photos, life history observations, etc. The authors of this paper use these “names” in later papers, further complicating the issue. Although these names are not what a taxonomist would traditionally consider a species name available for nomina nuda designation, I think that their original “designation” and later propagation in the literature fully warrants Brower’s paper rectifying these nomenclatural problems. I don’t like the idea of people describing species from Barcodes any more than you, and if he wasn’t trying to make a political point with this paper I’m sure the author would normally have examined the specimens and gone the more traditional route of species description using morphological characters. The precedent this paper sets is scary though…