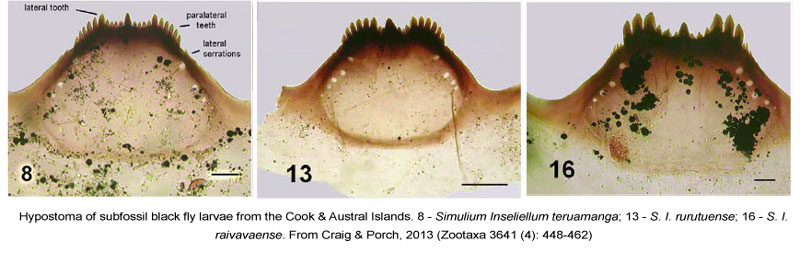

When identifying insects, the further you want to identify them, generally the smaller the morphological characteristics you need to look for are. For instance, to recognize the taxonomic order Diptera, you need only count the number of pairs of wings an insect has (usually…), but to identify a fly to species, you may need to hone in on the presence or absence of a single bristle on its thorax, or middle leg, or genitals. But what about species or populations where even these characters may be too similar to confidently tell distinguish, and where you could potentially be overlooking and unknown amount of diversity, better known as the elusive cryptic species? Well, you could look at their DNA, and try to see if there are any differences there, or, if you work on black flies, you could literally look at their DNA. Like, actually looking at the shape and patterning of their chromosomes, specifically special clumps of DNA found in larval black flies called polytene chromosomes.

Polytene chromosomes are the jumbo-sized versions of normal chromosomes only found in cells involved with secretion, and for whatever reason, are only present in springtails (Collembola) and true flies (Diptera). Rather than replicating and then splitting themselves up amongst a series of daughter cells like normal chromosomes, polytene chromosomes replicate themselves over, and over, and over again, sticking together in clumps of hundreds to thousands of complete chromosomal strands all woven together into a thick rope of genetic instructions. By banding together like this, these special chromosomes reveal all kinds of fascinating information about species and speciation.

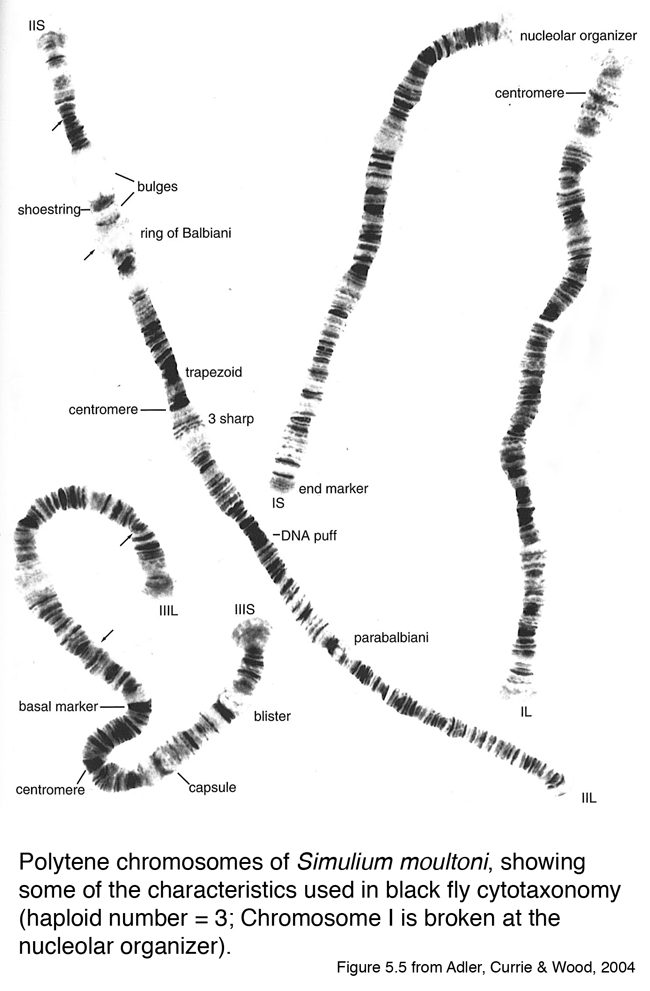

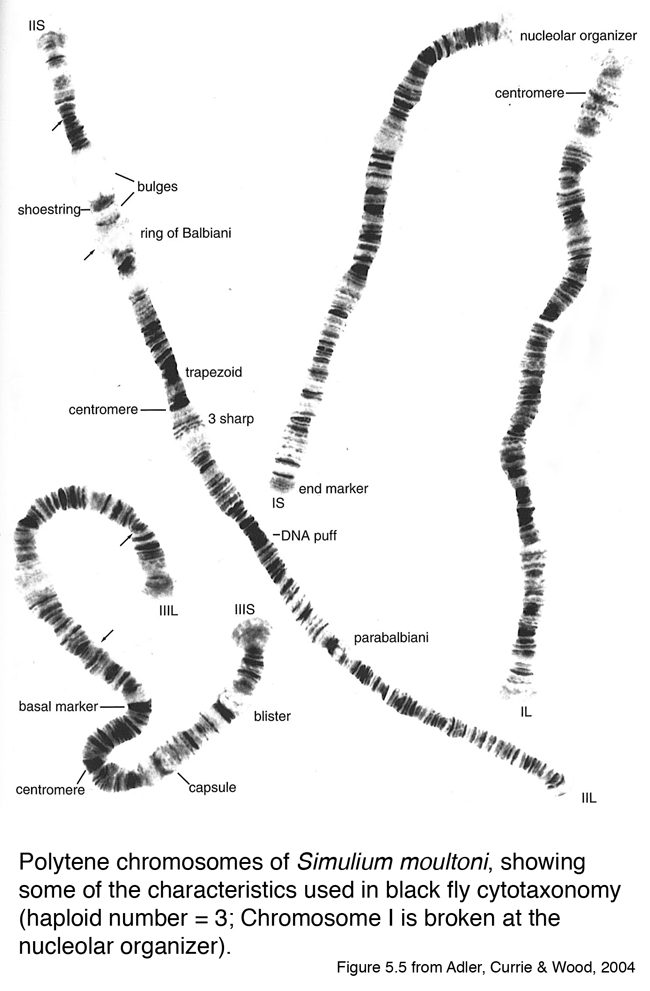

Starting in the 1930’s, while scientists were only just beginning to understand what chromosomes were and the role they played in genetics and heritability, dipterists began to notice that polytene chromosomes provided an untapped source of morphological characters to work with. Black fly taxonomists in particular latched onto this new dataset, largely because these over-sized chromosomes were easy to find in the silk glands of larval black flies, and provided a simple and low cost means of identifying species. Patterns of black and white bands, the locations and sizes of bulges, blisters, and rings of Balbiani all appeared to be conserved within populations and species, and with only 3 chromosomes to deal with, taxonomists, already tuned to look for the slightest differences and similarities between specimens, began to find all kinds of useful information; specific banding patterns that would be inverted in some species, but not in others; whole arms of chromosomes getting spliced onto the “wrong” chromosome; all three chromosomes getting jumbled up and stuck together in the middle like a genetic pinwheel with what they called a chromocenter.

By studying these “macrogenomes”, Simuliidae experts have been continuing to refine what a black fly species really is, and are beginning to unlock the mysteries of cryptic diversity.

Take, for example, work recently published by a group of black fly experts on the Old World subgenus Simulium (Wilhelmia). These flies originally came to the group’s attention due to an outbreak of black flies in Turkey which was driving down livestock production and tourism due to the sheer numbers of biting adults (those in Northern Canada can surely commiserate), and in order to figure out what species was responsible, decided to take a closer look. A much, much closer look, specifically at their polytene chromosomes.

After sampling larval black flies from across Europe, they discovered that what had recently been considered one generalist species found from England clear across the continent to at least Kazakhstan, Simulium (Wilhelmia) lineatum, was actually at least 3 species, each with unique differences in their chromosomes, and which replaced each other in streams as you head East!

Here you can see where the “actual” Simulium lineatum is found (blue) (although the authors note that something funny may be going on with the English specimen’s chromosomes, which could lead to further splitting), and where each additional species crops up as you move east, with Simulium balcanicum in green, Simulium turgaicum in red, and Simulium takahasii in yellow. The orange area without any data points is a void in the team’s data, but they have reason to suspect that several species recently described from China will fit into the pattern discovered in the west. Now that the team has worked out these basic limits for each species, they also hope to explore whether or not these species may be successfully mating with one another despite the differences in their chromosomes, or whether hybridization can occur between species pairs. All of this new information will in turn help us understand the intricacies of polytene chromosome taxonomy further, and continue to adapt black fly taxonomy to fit the total evidence available.

So by peering deep within the silk glands of black fly larvae, we can now weave together the ways in which simuliids diversified, and begin to understand the web of underlying mechanisms that make one species become two, or three, or more. It just goes to show that literally no matter how closely you look, there will always be surprises waiting to be found when it comes to fly taxonomy.

—-

Adler P.H., Alparslan Yildirim, Onder Duzlu, John W. McCreadie, Matúš Kúdela, Atefeh Khazeni, Tatiana Brúderová, Gunther Seitz, Hiroyuki Takaoka & Yasushi Otsuka & (2014). Are black flies of the subgenus Wilhelmia (Diptera: Simuliidae) multiple species or a single geographical generalist? Insights from the macrogenome , Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, n/a-n/a. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bij.12403

Adler, P.H., Currie, D.C., Wood, D.M. 2004. The Black Flies (Simuliidae) of North America. Cornell University Press. Ithaca, NY & London, UK. 939 pp.