UPDATE: It turns out my first theory involving oestrid bot flies was full of holes. I’ll leave it up because the biology of the individual parasites is accurate and interesting, but see the bottom of the post for an accurate description of what happened in the photo. I apologize for the misinformation.

Recently, I was catching up on Twitter late at night when @PsiWaveFunction shared a link to a photo on Reddit that stopped me cold in my tracks and that has kept me morbidly fascinated since. I’ve spent the better part of a day thinking about the photo, and I think I’ve pieced together the series of events and organisms that lead to the case of the mystery myiasis. If my theory is correct, this might be one of the coolest cases of parasitism I’ve ever encountered, and features a fly who’s life history beautifully illustrates the intricacies of evolution, another fly that’s threatening the birds which helped Darwin develop his theory of evolution through natural selection, and a bird who is being selected against by the worst possible luck.

Normally I’d include the photo in question right about here, but out of respect for those victims readers who are a tad squeamish at the sight of parasites (or birds), I’ll simply link to it and allow your curiosity to battle your better judgement1. I’ll give you a moment to decide and, should you accept the challenge, digest what you’ve just seen.

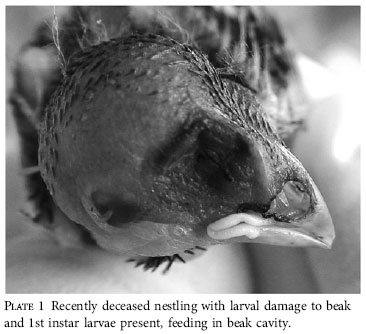

“This baby bird has no face… only maggots”

So, were you amazed? Disgusted? Wondering what the hell you were looking at? If you’re like me, you probably felt a little bit of all three, and then immediately went back to take a closer look.

Welcome to the wonderful world of warble flies (family Oestridae)! Each of those oddly formed lumps is actually a bot fly maggot which has burrowed beneath the skin of the chick to feed and develop. You’ll notice two dark marks on the exposed end of each maggot; these are the spiracles through which the maggot breathes. After a few weeks, each of the maggots will wriggle free from the bird, drop to the ground and pupate, eventually emerging as an adult ready to breed. Normally the host is left mostly unharmed after providing safe harbour for a bot fly, but in this case I suspect the bird might have problems due to the shear number of maggots present (at least 15 that I could make out).

What’s odd about this situation2 is that these bot flies have parasitized a bird. You see, almost all bot flies are mammal parasites, infesting anything from rodents to elephants, and are usually very specific about their host species. One bot fly however, Dermatobia hominis, is a generalist, and has been recorded infesting a number of different animals, from humans and monkeys to dogs and cats, and of relevance to this story, birds on occasion. In a family of narrow specialists, it’s a wonder that D. hominis is such a broad generalist; until you learn how D. hominis distributes its offspring — by hijacking other flies to serve as expedited egg couriers.

Psorophora sp. (Culicidae) with D. hominis eggs attached. Illustration by A. Cushman, Systematic Entomology Laboratory, USDA.

After mating, female D. hominis will snatch up other parasitic flies, like mosquitoes, flesh flies and muscid flies3, and lay a clutch of eggs on the enlisted fly. When the carrier fly locates and lands on a host to feed4, the body heat of the victim signals the bot fly egg to hatch and fall from the carrier onto its new home, where it quickly burrows in to begin feeding. This amazing life cycle means that the female bot fly has little control over where, and on what species, its offspring ultimately end up infesting, resulting in a nearly random generalist parasite that must be able to survive on whatever host it finds itself on, including our small bird.

Obviously the natural world is a complex system, and unfortunately for our bird, it’s full of a diverse array of parasites, all looking for a free meal. Let me introduce you to another player in this saga, Philornis downsi (Muscidae), a fly native to continental South America and Trinidad & Tobago, where our unfortunate bird lives.

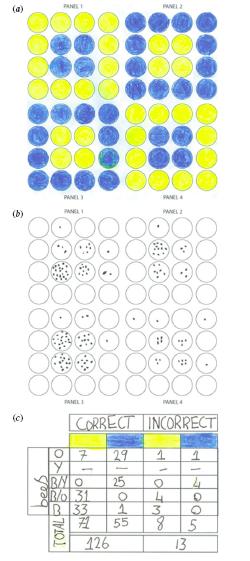

While adults are unassuming, feeding on pollen and nectar, Philornis downsi larvae are brood parasites of nesting birds. Hiding out of sight during the day in the bottom of the nest, maggots emerge after dark to crawl within the nasal passages of developing chicks, feeding on their blood and tissue, sapping their energy. As the maggots continue to grow, they begin feeding elsewhere on the nestlings, causing severe damage and ultimately death. Throughout the Galapagos, where the fly was introduced sometime prior to 1964, Philornis downsi has been causing nestling mortality rates as high as 95% in Darwin’s finches, the unique birds who’s diverse beak shapes inspired Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. While there has been a great deal of work done on P. downsi in the Galapagos in an effort to save these ecologically important birds5, I assume it is also receiving research attention in its native range, which is where we return to Reddit, our original photo and what I think happened.

Of all the parasites, in all the nest boxes, in all the world, she flies into mine.

The photo that began all this was uploaded to Reddit by marrgalo, who explained they found the bird while monitoring bird nests on Tobago for Philornis downsi as part of their research program. Tobago is also well within the range of Dermatobia hominis. Here’s what I think may have happened:

My theory was wrong. See below for information about the actual parasite.

A recently mated female Dermatobia bot fly was looking for a carrier flyA female Philornis downsi happened to fly by, was quickly snatched by the bot fly and entrusted with a load of bot fly eggsThe female Philornis was released, and continued her search for a bird’s nest to deposit her eggs inFinding a nest, the Philornis female walked around, laying eggs among the nesting material, and happened to tread across the young bird in the nest

The bot eggs, sensing the proximity of a warm-bodied host, hatched and quickly found their way to the unlucky bird’s faceThe Philornis female finished laying her eggs and took off from the nest, leaving chaos brewing in her wakeLater, a social media-conscious research assistant comes along, finds the disfigured nestling, and does the only logical thing; takes a picture and posts it to the internet for all to enjoy!

Of course, this is only a theory based on a single photo and a very small fraction of information about the team’s research, but given the evidence and biology of the species potentially involved, I think it’s certainly a plausible hypothesis. There are a lot of potential fallacies in my theory, like whether the bot fly larvae are actually Dermatobia, or whether Dermatobia even uses Philornis as a vector (although it’s known to use 11 species of Muscidae), but these are the sort of questions that can be observed and tested eventually. Hopefully the researchers behind the photo will rear the maggots from the bird’s face, identify the parasites involved, and then publish their work so I can find out whether any of these ideas turned out to be accurate6.

Whether my theories were correct or not, the fact that they’re even plausible keeps me interested and excited about entomology and the intricate roles parasites play in our daily lives!

References:

Eibel, J.M., Woodley, N.E. 2004. Dermatobia hominis (Linnaeus Jr., 1781) (Diptera: Oestridae). The Diptera Site. Accessed June 6, 2012. http://1.usa.gov/MbTexi

Fessl B, Sinclair BJ, & Kleindorfer S (2006). The life-cycle of Philornis downsi (Diptera: Muscidae) parasitizing Darwin’s finches and its impacts on nestling survival. Parasitology, 133 (Pt 6), 739-47 PMID: 16899139

O’Connor, J.A., Robertson, J. & Kleindorfer, S. (2010). Video analysis of host–parasite interactions in nests of Darwin’s finches, Oryx, 44 (04) 594. DOI: 10.1017/S0030605310000086

UPDATE June 7, 2012 @ 3:30PM EST: It turns out that the maggots in the bird’s face aren’t Dermatobia hominis, or even bot flies of the family Oestridae at all! After doing some further research, I’ve learned that they are more likely to be another species of Philornis fly. I was totally unaware that there were flies outside of the oestrid bot flies which burrow into the skin of hosts and form warbles like these, but it turns out there are.

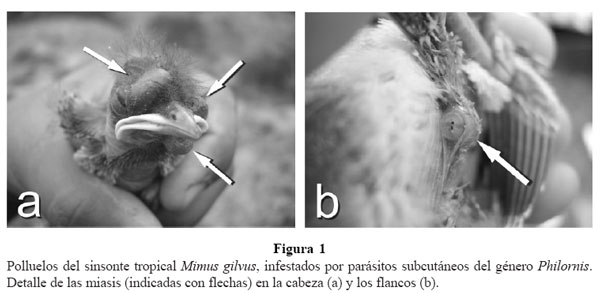

While Philornis downsi are ectoparasites that feed on nestling birds as I described, it seems that there are several species in the same genus which burrow within the skin and form welts similar to oestrid bot flies. Here’s an example of Philornis vulgaris infesting a Tropical Mockingbird nestling from Colombia:

Looks vaguely familiar no? I think it’s safe to say now that this is what happened in the original photo and not the complex tale of 2 parasites like I described above.

I’m incredibly embarrassed by my Taxonomy Fail here (which holds a TFI of 11.3). Although the biology of the two parasitic species I originally discussed are accurate, the chances of them having anything to do with one another appear to be unlikely. I sincerely apologize for publishing a story that spread such inaccurate information, and I’ll do my best to not let it happen again.

Note to self: don’t assume you know anything, especially when it involves parasites.

On the bright side, I learned something new about Diptera (and humility) today, and we can all rest comfortably knowing that there are multiple, unrelated groups of flies that get under the skin of their hosts. Because I’m sure that makes everyone feel better.

More information about subcutaneous Philornis:

Amat, E., J. Olano, F. Forero & C. Botero 2007. Notas sobre Philornis vulgaris (Couri, 1984) (Diptera: Muscidae) en nidos del sinsonte tropical Mimus gilvus (Viellot, 1808) en los Andes de Co- lombia. Acta Zoológica Mexicana, 23(2): 205-207. http://bit.ly/LwsHh1

Uhazy, L.S., Arendt, W.J. 1987. Pathogenesis associated with philornid myiasis (Diptera: Muscidae) on nestling pearly-eyed thrashers (Aves: Mimidae) in the Luquillo Rain Forest, Puerto Rico. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 22 (2): 224-237. http://bit.ly/KlXBGR

—————————

1- If you can’t decide, I vote you click and look. You can thank me later.

2- Beyond the whole face-of-a-million-maggots of course.

3- Among other groups including blow flies and even ticks.

4- Something these blood-sucking flies have evolved to do quite well obviously. The fact that bot flies “cheat the system” in this regard, getting their eggs to their host without needing to invest energy in complex host-finding senses, just goes to show that nothing is more awesome than evolution in action.

5- See O’Connor et al. 2010 for a good synopsis of work and observations, and check out some of the videos she’s posted to YouTube of the maggots interacting with nestlings.

6- If you happen to have research contacts in Tobago who might know about work being done on Philornis, can you let them know I’m curious? Thanks.