Yesterday marked the 100th anniversary of the extinction of one of our most iconic emblems, the Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius). The web is alive with tributes to Martha, the final individual of her species, and cautionary tales of conservation and how we should be working to prevent this happening to any other species. There has also been considerable discussion and debate recently whether the Passenger Pigeon may be a candidate for “de-extinction”; the theoretical process of bringing a species back from the void through cloning and genetic engineering. Seeing how I generally dislike vertebrates dominating the biodiversity news cycle, I figured we could all use a slightly less depressing story about extinction, de-extinction, the role of natural history museums in conservation, and of course, taxonomy.

As we’re beginning to understand, no species is an island unto itself. Every individual is an ecosystem of parasites, predators and symbionts, and thus when one species disappears, its co-dependents are just as likely to vanish, usually without us even realizing it. Allow me to share the story of Columbicola extinctus, a chewing feather mite that quietly faded into the night likely years prior to Martha’s high-profile demise on September 1, 1914, and which we only learned about 20 years after that.

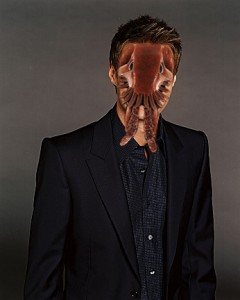

Columbicola columbae, a species closely related to Columbicola extinctus (it seems the differences between them are slight modifications of the head and genitalia; feel free to use your imagination). Photo by Vince Smith, used under CC-BY license.

Working from a preserved Passenger Pigeon specimen collected in 1895 and housed in the Illinois Natural History Survey, Richard Malcomson discovered and described Columbicola extinctus in 1937, noting he had only seen 15 specimens of this new louse. In what may be the saddest etymological discussion I’ve seen, Malcomson says:

“Dr. Ewing of the National Museum, Washington, D.C., suggested the name of extinctus which surely is a suitable one for the Passenger Pigeon is now extinct and probably has carried the parasite into extinction with it.”

And so humanity carried on, parading the Passenger Pigeon out as the flag-bearer for extinction, while its lowly louse faded from memory. That is, until 1999, when, like a phoenix louse rising from the ashes of its host, Columbicola extinctus out-lived its name. While reviewing the genus Columbicola, Dale Clayton and Roger Price discovered that Columbicola extinctus wasn’t found solely on the Passenger Pigeon, but was in fact still alive and well on the Passenger Pigeon’s closest living relative, the Band-tailed Pigeon (Patagioenas fasciata)! What’s more, Columbicola extinctus was found on Band-tailed Pigeon specimens collected all up and down the Pacific coast, from California to Peru! As Clayton & Price note

“Our study reveals no consistent differences between Columbicola specimens from the extinct passenger pigeon and those from the extant band-tailed pigeon, C. fasciata. Thus, there is no longer grounds for considering this species of louse extinct, despite its unfortunate specific epithet.”

It’s worth considering how bird specimens preserved and maintained in a natural history museum allowed taxonomists to not only find a species at a time when it was believed to be extinct, but to also resurrect that same species 60 years later, redefining the term “de-extinction” before it was trendy. Sure, Columbicola extinctus’ species epithet may be a little premature, but it also serves as an important reminder that while extinction is usually forever, nature sometimes finds a way.

And should someone ever succeed in bringing the Passenger Pigeon back from extinction (however unlikely that is or may be to occur), we’ll be able to reunite two species who’s lives and legacies were intimately intertwined, and who were each thought to be lost to time and humanity. A fairytale ending if ever I’ve heard, albeit one that probably won’t make it to Disney.

—

Clayton D.H. & Price R.D. (1999). Taxonomy of New World Columbicola (Phthiraptera: Philopteridae) from the Columbiformes (Aves), with Descriptions of Five New Species, Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 92 (5) 675-685. DOI:

Malcolmson R.O. (1937). Two New Mallophaga, Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 30 (1) 53-56. DOI: