Today is my 1 year Twitterversary, making it as good a time as any to share why I think Twitter is one of the most important resources available to scientists, how to make the most of it, and what makes it great for interacting with non-scientists.

Today is my 1 year Twitterversary, making it as good a time as any to share why I think Twitter is one of the most important resources available to scientists, how to make the most of it, and what makes it great for interacting with non-scientists.

Twitter is as simple a social network as you can get, “limited” to text-based updates of 140 characters telling people “What’s Happening” in your life. But as they say, it’s not the size of the tweet that matters, but rather how you use it, and there are roughly 2 million ways in which to interact with the Twitterverse, sharing and finding all manner of relevant content, ideas, and information!

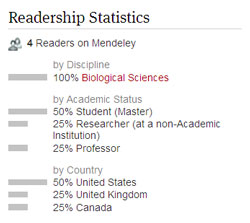

So what makes Twitter the ultimate scientific resource? Networking. If there’s one thing I’ve realized about academia, it’s that what you know is not all that matters when it comes to finding opportunities (although it is extremely important). Many times it also matters who you know, and maybe more importantly, who knows you! Through Twitter I’ve “met” entomologists of all disciplines; apiculturists, IPM consultants, taxonomists, ecologists and physiologists across the spectrum of amateurs, graduate students, post-docs, museum staff or university faculty. But I’ve also interacted with individuals who I would normally never come in contact with, like marine biologists, scientific illustrators, botanists, bioinformaticians, evolutionary biologists, statisticians, microbiologists and many, MANY science writers! Joshua Drew (a marine biology post-doc in Chicago) hit the nail on the head:

These people won’t be at the usual conferences I attend, but that doesn’t mean my research isn’t related to theirs. By exposing myself to a wide array of scientists, I have found inspiration to apply to my own projects, methods to experiment with in future, and kindred spirits who are also working their way through the trials of academia and provide invaluable advice. As I move forward, who knows how these individuals may influence my career, with each “tweep” a potential collaborator, advisor or hiring committee member; fortune favours the prepared, and Twitter has allowed me to diversify my knowledge base significantly, better preparing me for future research obstacles.

With over 200 million users posting more than 95 million tweets per day, you may find it daunting to discover tweeters relevant to your field of science. Luckily there are several ways to get the most out of Twitter with minimal time investment. You can easily subscribe to lists of scientist twitter users, or super-tweeters like @BoraZ who share content from a wide variety of scientists (or you can start with who I follow even). It’s important to note that when you follow someone on Twitter, the information being shared is unilateral, meaning you can see what that person posts, but they don’t see what you post (unless they reciprocate and follow you). This means you can tailor the information you receive to only those you find interesting, without getting inundated with updates by all the people who may follow and interact with you.

However, to unlock the real power of Twitter, I recommend exploring the #hashtag. Integrated by Twitter as an automatic search term, hashtags allow you to filter tweets from all 200 million+ users simply and directly. There are a number of interesting and widely adopted science hashtags which may interest you, but you can create, use and follow any hashtag which you consider interesting or relevant (like #Diptera, or #ScienceShare perhaps). There are 2 in particular however which I have found to be the most powerful; #madwriting and #IcanhazPDF.

#madwriting is a rallying call for those that may struggle with writing or dedicating the time to do so. Created to develop a shared sense of community, accountability and encouragement, #madwriting bouts last about 30 minutes, and encourage undistracted writing, followed by a sharing of progress after the time is up. Major portions of my Master’s thesis were accomplished thanks to the #madwriting community, as well as numerous blog posts (including this one).

Although grammatically terrible, #IcanhazPDF is the most useful hashtag for scientists in my opinion. If you or your institution does not have access to a journal, it can be frustrating, time-consuming and difficult to obtain a copy of a paper. Traditionally this obstacle would be overcome using interlibrary loan or contacting authors or other colleagues at different institutions and requesting copies directly. With #IcanhazPDF, the Twitter community has changed the game, crowd-sourcing paper requests from complete strangers across the world. The speed at which you can obtain a paper has now gone from days or weeks to minutes, allowing you to go on with your research & writing without delay. I can personally attest to this system, having made a request last spring and receiving the PDF via email less than 20 minutes later. While no different from making direct requests from colleagues (which has gone on for decades), there is the potential for legal trouble, so be sure to make an informed decision before taking part.

As you can see, there are numerous ways for scientists to benefit from Twitter, but Twitter is also a great way to reach out to the general public and give back. Whether you share tales from your research (or more personal stories that demonstrate that scientists are human too), pass along links to popular science articles or blog posts (or even open-access journal articles), develop citizen science projects, or simply interact with the public by answering questions, it’s easy to give back on Twitter and potentially inspire future generations of scientists. I’ve helped identify insects for people, provided answers on biodiversity, and tried to change people’s opinions about flies in general, all via Twitter. The 140 character limit I mentioned earlier has also forced me to become more concise with my writing, and lead me to change my use of verbose terms common to scientific jargon. I can also see Twitter being incorporated in the classroom, facilitating interactions between students and teachers/professors or being used as extra credit (recording wildlife sightings, extracurricular readings, etc).

While I understand scientists are busy people and may be hesitant to join a(nother) social network, I feel that careful integration of Twitter into a research program can actually increase productivity and innovation. If you’re not already tweeting, I encourage you to give it a chance and explore what you may be missing!

You can find me on Twitter @BioInFocus.

UPDATE (Jan. 3. 2011, 00:30): @BoraZ sent me a link to another great clearing house of science twitterers, Science Pond. At this time their tweet display algorithm seems to be down, but you can still browse the long list of scientist users on the left hand side.