A few days ago I was walking through the University of Guelph Arboretum taking some down time and trying to get back into the photography groove when I noticed a peculiar sight…

The trees were weeping, and dozens of flies were lapping up the sweet, sweet tears! Since there were several of these patches on two nearby trees (my tree bark ID skills are severely lacking, I’m a leaf man) and the wet marks were 4 to 10 feet off the ground, I felt it was a safe guess that it wasn’t a territorial marking (unless the UofG men’s basketball team was having a summer camp…), and last I checked I wasn’t in Fangorn Forest, so I did a little detective work to discover the story behind the sadness.

Closer inspection revealed these curious holes:

My first thought was to scan for long-horned beetles (Cerambycidae) or perhaps metallic jewel beetles (Buprestidae), but after seeing nothing but flies and wasps, I took a closer look and noticed that the holes only pierced the bark, and not the xylem (aka sapwood). It dawned on me that what I was looking at was a tricky, sticky lure set by a bird I’d seen plenty of times before in the Arb; the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus varius). This crafty woodpecker will cause superficial injuries to a tree, and then sit back while the sap flows free. The bird will then return to the tree and pick off the insects which are feeding on the sap, as well as some of the sap itself! Clever bird…

Pretty cool biology, so I took the opportunity to see what sort of insects were at risk of becoming an early spring brunch for the hungry sapsucker.

I observed a few butterflies when I first approached the trees, but they quickly flitted away, not to return while I was there. I’m by no means a Leper (i.e. a Lepidopterist), but I think they may have been Red Admirals (Vanessa atalanta, Nymphalidae), which are one of the earlier butterfly species to be found in Southern Ontario.

There were a number of hymenopterans taking advantage of the Saturday afternoon bounty including many Ichneuomoid wasps and this fuzzy female:

This andrenid bee (Andrenidae) seemed quite content to sit and lap up the sugary sap running down the tree bark, not caring when I moved in and out trying to get a decent photograph of it’s amazing hairdo.

While the bee was busy enjoying a solitary meal, this sawfly (Dolerus unicolor, Tenthredinidae) was more than happy to share the sap with a couple of calyptrate flies (a blowfly [Calliphoridae] on the right and what I believe to be a Muscidae at the top). In fact, the calyptrates made up the vast majority of the insects visiting the tree, in some places packed so tightly you couldn’t see the tree for the flies!

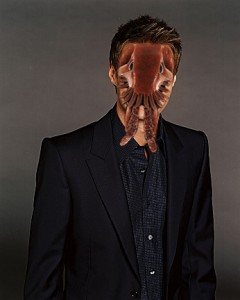

The sponge-like mouthparts found in many calyptrates are well demonstrated in this blowfly (Calliphoridae, possibly subfamily Chrysomyinae). You can see the maxillary palpi sticking straight ahead as the membranous labrum and associated sclerites mop up any residual tree sap on the bark.

Another, lesser known calyptrate family was also making an appearance; the Scathophagidae. I could make out what looked to be two species of scathophagid, including this Scathophaga sp. perched nearby awaiting its turn at the sugar shack.

Not everything went according to plan on this outing however, as I made a major n00b move – I forgot to pack specimen vials! While normally I’d have a dozen or so snap-top vials in my camera bag in case I ran into something which needed to be examined at a later date and added to the University of Guelph Insect Collection, after transferring my photo equipment into my new camera bag (courtesy of the best wife ever), I neglected to throw in the vials! The first rule of entomology (besides “ALWAYS talk about entomology”) is to collect the damn specimen, and as luck would have it, I came across a fly which I instantly wanted to collect (pictured above & below).

This Tachinidae caught my eye right away, and after several attempts, I managed to get a couple of decent images. Unfortunately, tachinid flies are one of the most diverse groups of animals on the planet, and the specimen would be vital in identifying it to the genus or subfamily level on my own. A lesson learned, and needless to say I threw a couple of vials in my bag as soon as I got home!

After getting my fill of photos and not having any means to collect some specimens, I decided to pull back and let nature take it’s course. While I never saw the sapsucker, I certainly appreciated the opportunity it created, allowing me to photograph a great diversity of flies and wasps!

When it comes to insect pests, few have been so devastating yet controlled and managed as the Boll Weevil (Anthonomus grandis). An introduced pest of US cotton in the early 20th century, the Boll Weevil has largely been eradicated thanks to a massive effort by the USDA (which might explain why there are only 4 photos of this beetle on BugGuide).

When it comes to insect pests, few have been so devastating yet controlled and managed as the Boll Weevil (Anthonomus grandis). An introduced pest of US cotton in the early 20th century, the Boll Weevil has largely been eradicated thanks to a massive effort by the USDA (which might explain why there are only 4 photos of this beetle on BugGuide).