NASA has called a big news conference for this afternoon to discuss a new discovery in the field of Astrobiology (the science of extraterrestrial life) for this afternoon at 2pm. Leaked stories are reporting that NASA scientists have discovered a new life form in Mono Lake, California. Reportedly this life form is arsenic-based, unlike every other animal, plant, fungi and bacteria on the planet which is phosphorous-based. Tune in here to watch along.

NASA has called a big news conference for this afternoon to discuss a new discovery in the field of Astrobiology (the science of extraterrestrial life) for this afternoon at 2pm. Leaked stories are reporting that NASA scientists have discovered a new life form in Mono Lake, California. Reportedly this life form is arsenic-based, unlike every other animal, plant, fungi and bacteria on the planet which is phosphorous-based. Tune in here to watch along.

The implications of such a find are beyond huge, if true! Does this mean life on Earth has arisen twice in 2 totally different ways (take that ecology and niche partitioning)? Is it extraterrestrial seeding (is the truth really out there)? Either way, phylogenetics and the taxonomic structure as we currently know it (Domain, Kingdom, Phylum, etc) has no room for independently derived life forms, necessitating an entirely new and parallel taxonomic lineage. Not to mention the fact that if it’s happened here there is no reason to assume that it hasn’t happened someplace else in the universe!

I’ll be live-blogging throughout the news conference and trying to provide insights into what this means for taxonomy and science in general. Stay tuned as the world learns of this new life! I encourage everyone to join the discussion below in the comments! Until then, live long and prosper and let the force be with you! (You knew the geek quotes were coming at some point didn’t you?)

Update (1:30pm, Dec 2, 2010): The cat’s out of the bag, and it’s certainly not the white tiger it was made out to be. While the early media reports I read ranged from the extremes of NASA actually finding life on other planets to the story I reported above, in actuality researchers did not discover a new arsenic-based life form, but rather forced an extremo-phile bacteria from Mono Lake to survive on arsenic rather than phosphorous. Even then there are conflicting reports on how much arsenic the bacteria are actually incorporating into their biochemistry. Needless to say I’m fairly disappointed, but I’ll leave that for a more in depth discussion later this afternoon. I’ll still be reading the paper and watching the news conference in case there is something interesting to report, but don’t expect a new taxonomic hierarchy this week!

Update (2:30pm, Dec 2, 2010): Well, that confirms it. The bacterial strain in question (GFAJ-1) was found to live in the mud of Mono Lake, where the concentration of arsenic is higher than most other aquatic habitats, and the researchers decided to see how far they can push the bacterium’s flexibility in accepting arsenic. By slowly weaning bacterium cultures from high phosphorous-content growth medium to low phosphorous-content they found the bacteria could survive and incorporate arsenic into the different cellular and molecular components necessary for life (nucleic acids, proteins, etc).

Update (2:35pm, Dec 2, 2010): I’m going to be candid here, and point out that the lead researcher, Felisa Wolfe-Simon, is coming across as really condescending. I imagine she’s trying to relate her results in a way that laypeople can easily understand (including referring to these bacteria as “bugs”… science fail) but her inflection and attitude is coming across as condescending in my mind.

Update (2:45pm, Dec 2, 2010): They’ve brought a phosphorous expert in who is going on and on about the potential for using arsenic-based life forms to solve the impending phosphorous shortages caused by the agricultural revolution. Not sure how he expects to incorporate arsenic-laden plants into our diet, seeing as it’s extremely toxic as repeatedly stated throughout the news conference. That’s also assuming that you could get non-arsenic adapted plants to accept it in the first place (remember, toxic).

Update (2:50pm, Dec 2, 2010): That was patriotic. She just made clear that all this research was done by Americans, on American soil, and using American dollars. I wonder if she’s worried about US congress criticizing her work on astrobiology like ant workers were criticized for working on ants from outside of the US of A!

Update (3:00pm, Dec 2, 2010): I believe it was USA Today that just phoned in and called out the research team of over-hyping their research and the reaction of the readers looking for proof of alternate life or aliens! I’ve got to agree with them on that (and I’ll bring that up when this circus is over). The researcher’s reply even included a plot line from Star Trek to explain how, although they didn’t find aliens, they now have more options when searching for life.

Final Update and Opinions: That brings this underwhelming scientific discovery to a close. When I first came across the story this morning, I was in awe that perhaps we’d have definitive proof of independently evolved life (whether native to Earth or elsewhere) and all of the implications I outlined originally. As more and more of the research was made available however, I couldn’t help but become frustrated and disappointed, not only with the media (which I expect to sensationalize news to garner attention), but especially with the scientists who allowed and, in some sense, promoted this wild speculation to increase their exposure. Is it any wonder that a large portion of the general public is dubious of science and it’s “wild” and “exaggerated” claims on climate change, extinctions, and now life? Perhaps it’s because I come from a scientific field that is largely ignored by the populace, but grandstanding with big claims and minor results seems like a waste of everyone’s time. Sure there are pressures on young researchers to establish a reputation for themselves, but at who’s expense? Their colleagues? The media? Or worst of all, the public? I’m of the firm belief that your science should speak for itself, without needing to resort to wild media campaigns, vague releases promising big results, or the fall back of “this has so much future potential”.

With that rant aside, I do think that this research is exciting (in a different way than originally), especially if they are able to back up their claims on the full integration of arsenic into biological systems. I’ve long been a believer that there is life in the universe beyond Earth, and have always been confused by astrobiologists saying that finding the exact conditions believed to be necessary for life (oxygen, phosphorous, liquid water, etc) are like a needle in a haystack. Why can’t something evolve to exploit a silicon environment where the mean daily temperature is 100°C? It’s often said that nature abhors a vacuum, so why provide limits on what conditions you believe are required for life to survive? This research lays the groundwork that these alternate hypotheses on the origins of life are feasible and that although alien life is still a matter for science fiction, the day is quickly approaching when we’ll be able to accept an independently evolved life form as scientific fact.

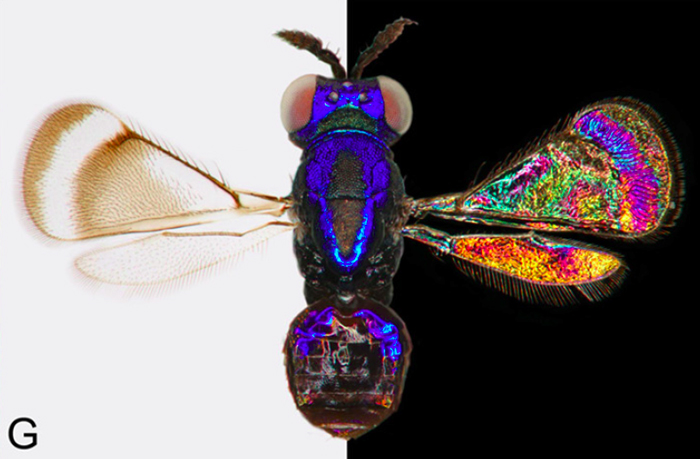

Today marks the birthday of one of the most influential and important insect authors; Robert Evans Snodgrass (1875-1962). Snodgrass’ special interest was insect morphology, especially within an evolutionary context, as he sought to not only understand how insects are put together, but also how those structures contributed to the evolutionary history of species. His 1935 opus, Principles of Insect Morphology, is still relevant in many regards (my 4th year Insect Physiology professor referred to it several times throughout the semester), and can be considered one of the most important entomology texts of the 20th century.

Today marks the birthday of one of the most influential and important insect authors; Robert Evans Snodgrass (1875-1962). Snodgrass’ special interest was insect morphology, especially within an evolutionary context, as he sought to not only understand how insects are put together, but also how those structures contributed to the evolutionary history of species. His 1935 opus, Principles of Insect Morphology, is still relevant in many regards (my 4th year Insect Physiology professor referred to it several times throughout the semester), and can be considered one of the most important entomology texts of the 20th century.