Taxonomist Appreciation Day has just come to a close where I am, and it was a lot of fun to see so many people express their thanks for the work that taxonomists do. I highly recommend browsing through the hashtag #LoveYourTaxonomist on Twitter, and seeing what people had to say.

I thought it might be interesting to take a look at what taxonomists were up to on this holiest of days. Personally, I reviewed a really great manuscript about an exciting new species of fly that I can’t wait to talk about more when it’s published, but here’s a quick run down of the new animal species* that were officially unveiled to the world on March 19, 2014.

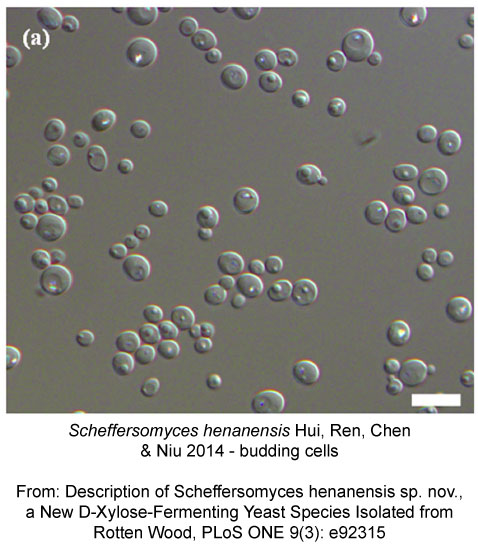

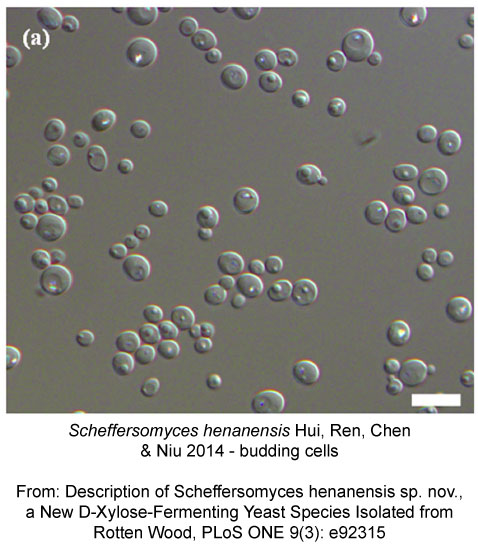

We’ll start small with a new species of yeast, Scheffersomyces henanensis, described from China today.

Ren Y, Chen L, Niu Q, Hui F (2014) Description of Scheffersomyces henanensis sp. nov., a New D-Xylose-Fermenting Yeast Species Isolated from Rotten Wood. PLoS ONE 9(3): e92315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092315

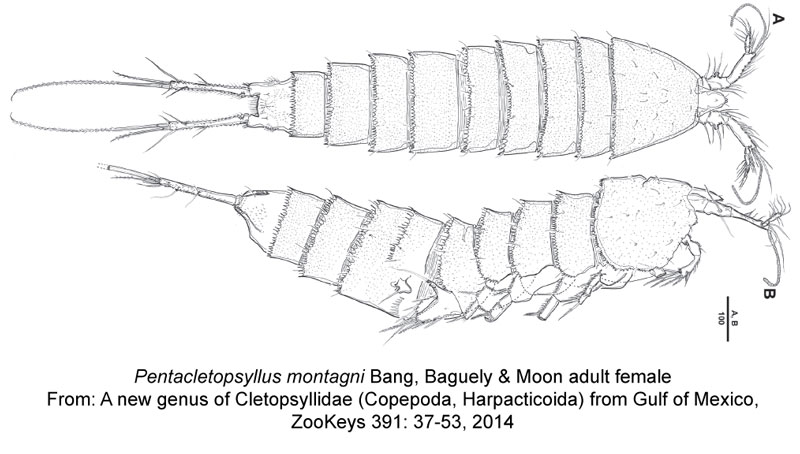

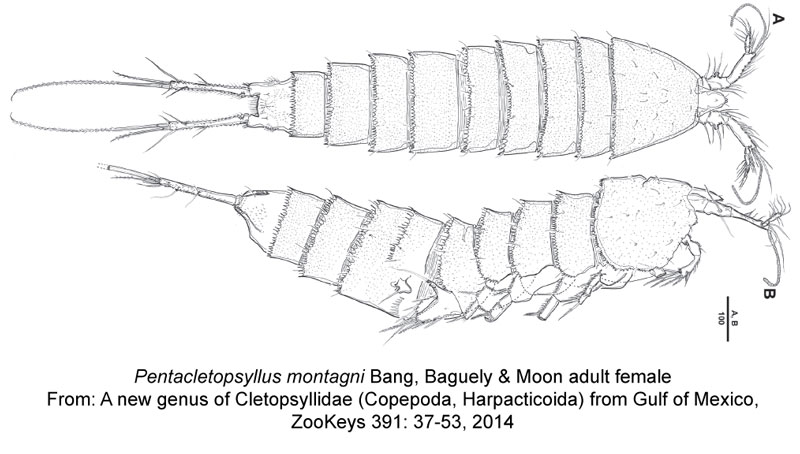

This charming creature is Pentacletopsyllus montagni, a benthic copepod that was found deep in the Gulf of Mexico.

Bang HW, Baguley JG, Moon H (2014) A new genus of Cletopsyllidae (Copepoda, Harpacticoida) from Gulf

of Mexico. ZooKeys 391: 37–53. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.391.6903

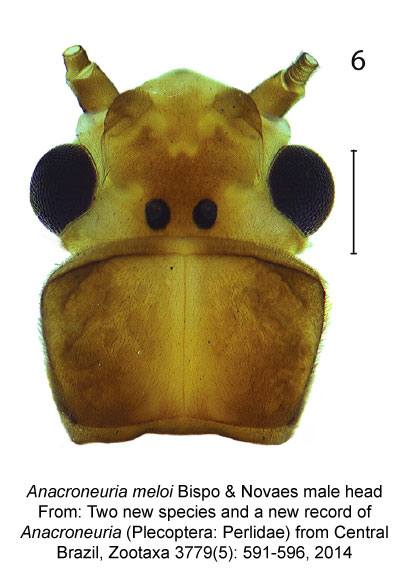

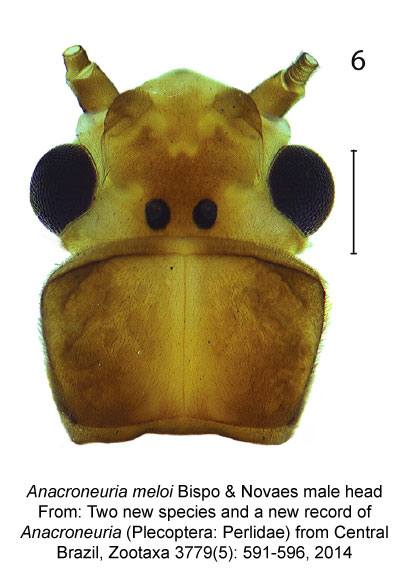

Allow me to introduce you to Anacroneuria meloi, a Brazilian stonefly named for the person who collected it (Dr. Adriano Sanches Melo). This was one of two new species described in this paper.

Bispo, Costa & Novaes. 2014. Two new species and a new record of Anacroneuria (Plecoptera: Perlidae) from Central Brazil. Zootaxa 3779(5): 591-596. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3779.5.9

This odd looking creature, Hydrometra cherukolensis, is actually a true bug! The eyes are the bulges in the left third, and like all hemipterans, they have sucking mouthparts tucked under the head (not visible in this photo). The authors of this study described another species of these strange looking bugs as well.

Jehamalar & Chandra. 2014. On the genus Hydrometra Latreille (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Hydrometridae) from India with description of two new species. Zootaxa 3977(5): 501-517. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3779.5.1

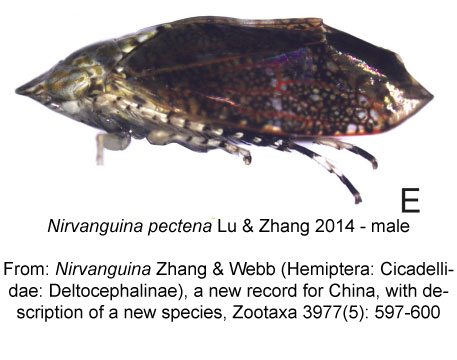

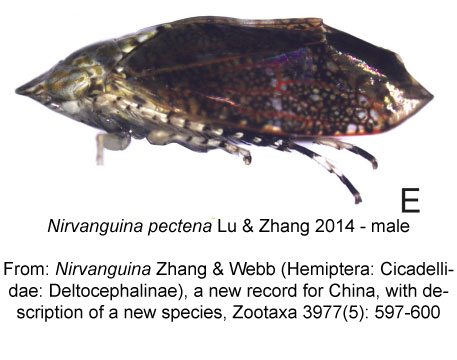

This little leafhopper, Nirvanguina pectena, is only 1/2 centimetre long!

Lu, Zhang & Webb. 2014. Nirvanguina Zhang & Webb (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae: Deltocephalinae), a new record for China, with description of a new species. Zootaxa 3977(5): 597-600. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3779.5.10

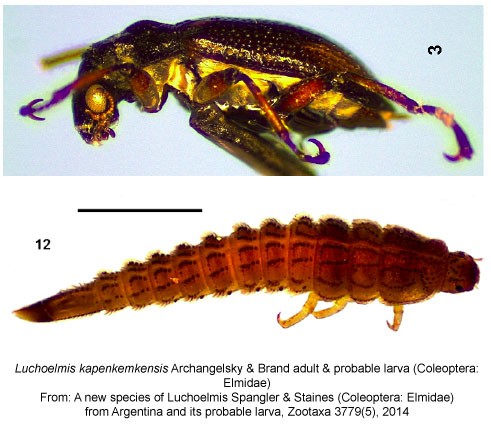

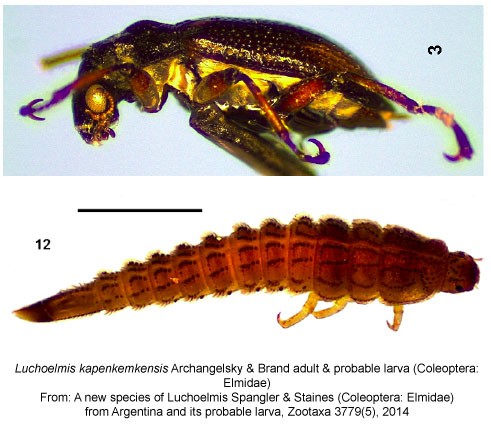

Not only was Luchoelmis kapenkemkensis described, but so was it’s (probable) larva, an unusual occurrence for insects.

Archangelsky & Brand. 2014. A new species of Luchoelmis Spangler & Staines (Coleoptera: Elmidae) from Argentina and its probable larva. Zootaxa 3977(5): 563-572. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3779.5.6

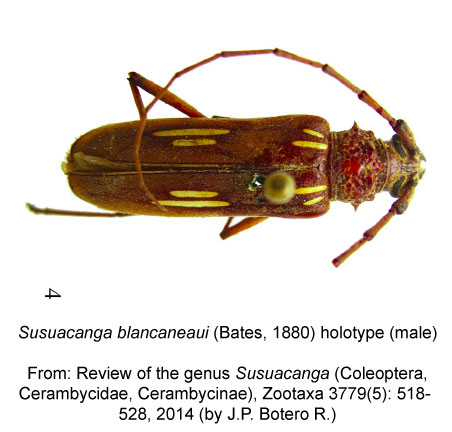

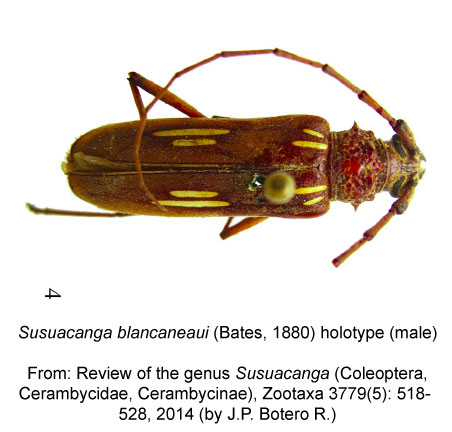

While not a new species, Susuacanga blancaneaui was transferred into the genus Susuacanga from the genus Eburia today. Taxonomists don’t just find new species, they also reorganize genera and species as they gain a better understanding of variations within and relationships between taxa.

Botero R, JP. 2014. Review of the genus Susuacanga (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae, Cerambycinae). Zootaxa 3977(5): 518-528. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3779.5.2

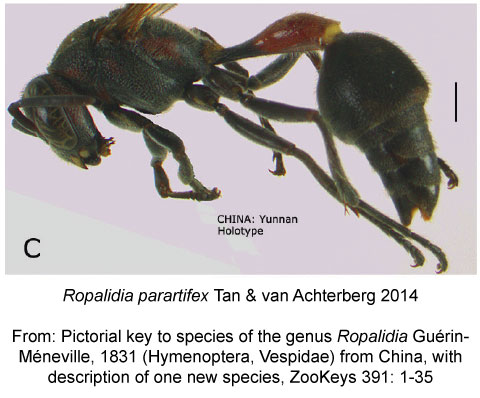

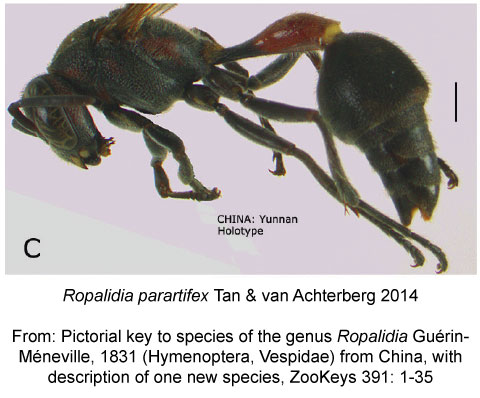

The authors of this study not only described a new species of wasp, Ropalidia parartifex, but they also produced a wonderfully illustrated identification key to help others recognize these wasps, as well as recording 6 species previously unknown to occur in China.

Tan J-L, van Achterberg K, Chen X-X (2014) Pictorial key to species of the genus Ropalidia Guérin-Méneville,

1831 (Hymenoptera, Vespidae) from China, with description of one new species. ZooKeys 391: 1–35. doi: 10.3897/

zookeys.391.6606

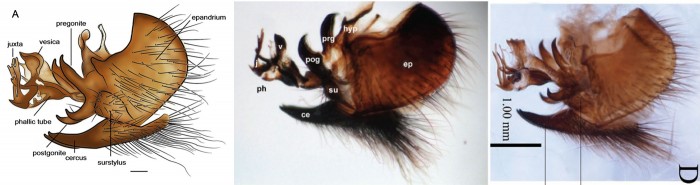

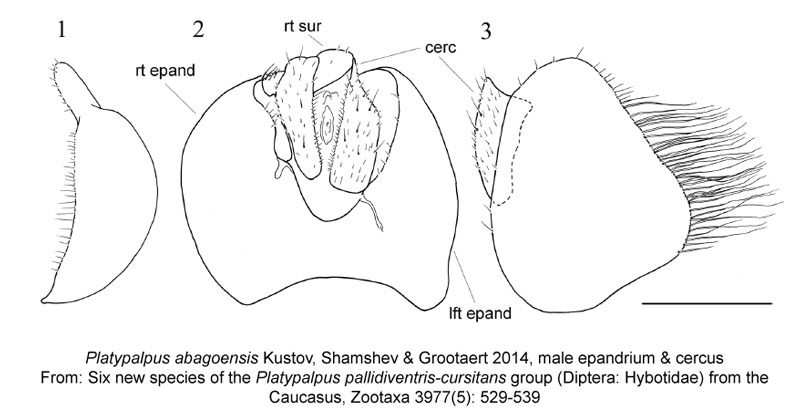

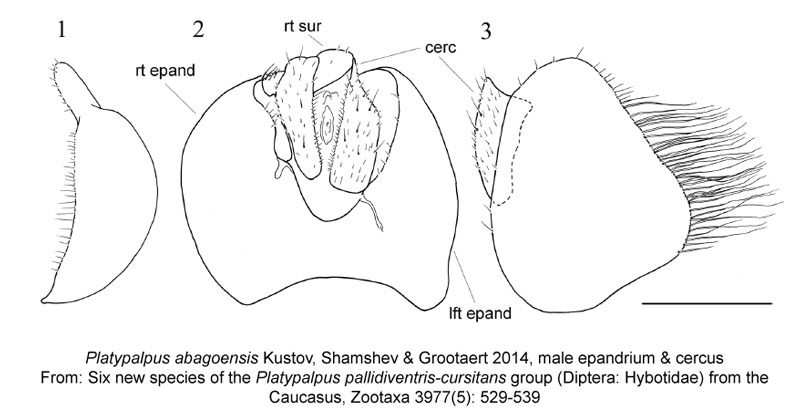

Not only do taxonomists have to be able to recognize new species, they often also need to be able to illustrate how they’re different from one another. Here, the authors drew the final abdominal segments of a male Platypalpus abagoensis to demonstrate how it differs compared to the other 5 new species they were describing; the true intersection of art and science!

Kustov, S., Shamshev, I. & Grootaert, P. 2014. Six new species of the Platypalpus pallidiventris-cursitans group (Diptera: Hybotidae) from the Caucasus. Zootaxa 3977(5): 529-539. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3779.5.3

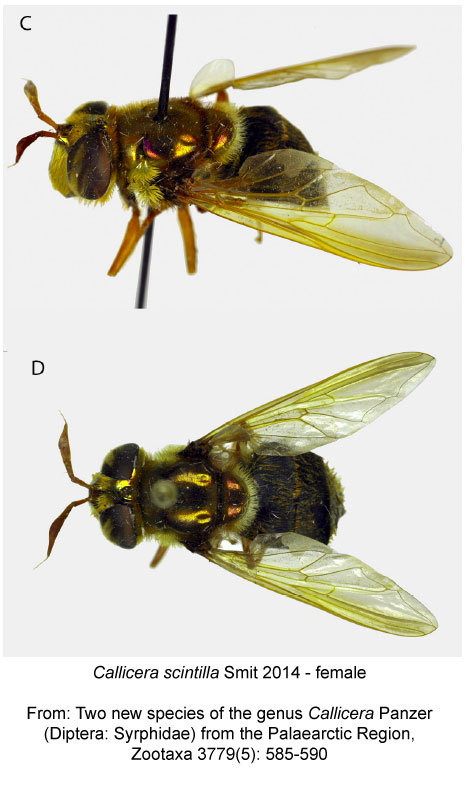

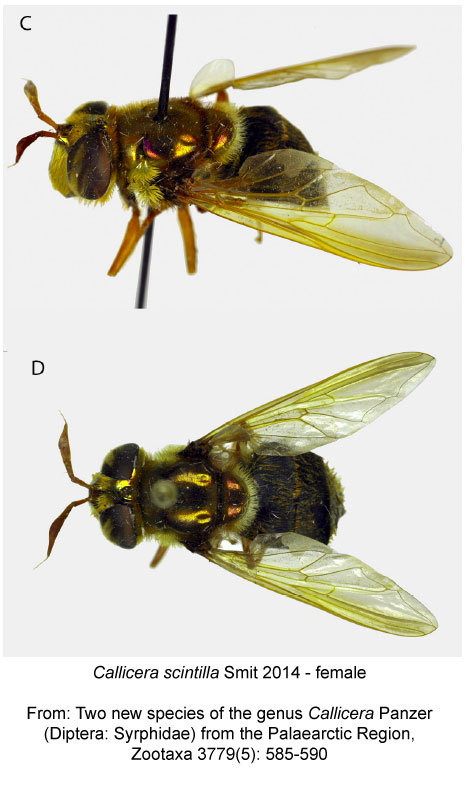

Perhaps the most striking new species described today, Callicera scintilla‘s species epithet literally means glimmering or shining in Latin. Another species was also described in this study, but alas, it isn’t a shiny copper.

Smit, J. 2014. Two new species of the genus Callicera Panzer (Diptera: Syrphidae) from the Palaearctic Region. Zootaxa 3977(5): 585-590. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3779.5.8

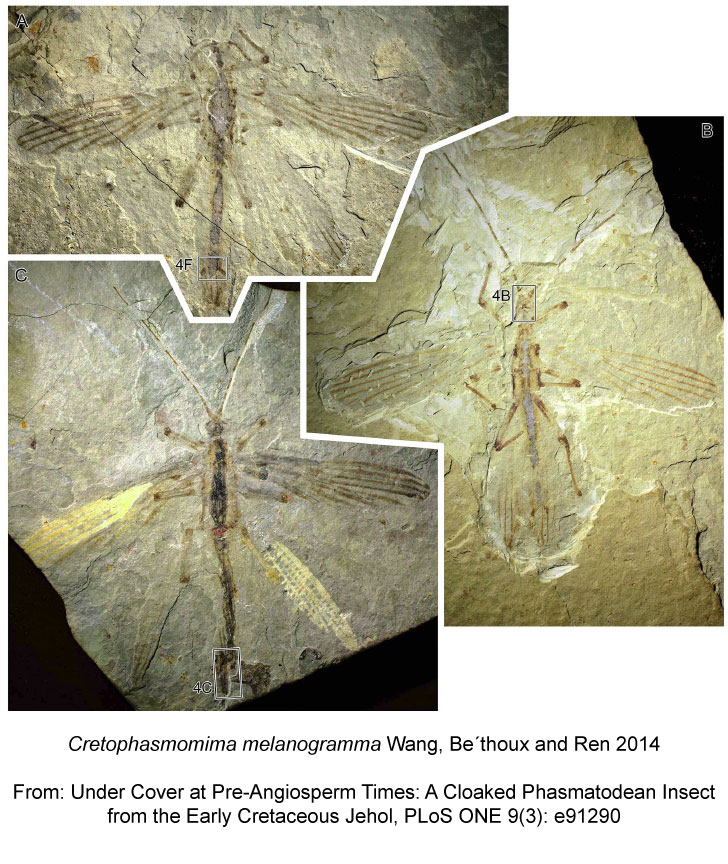

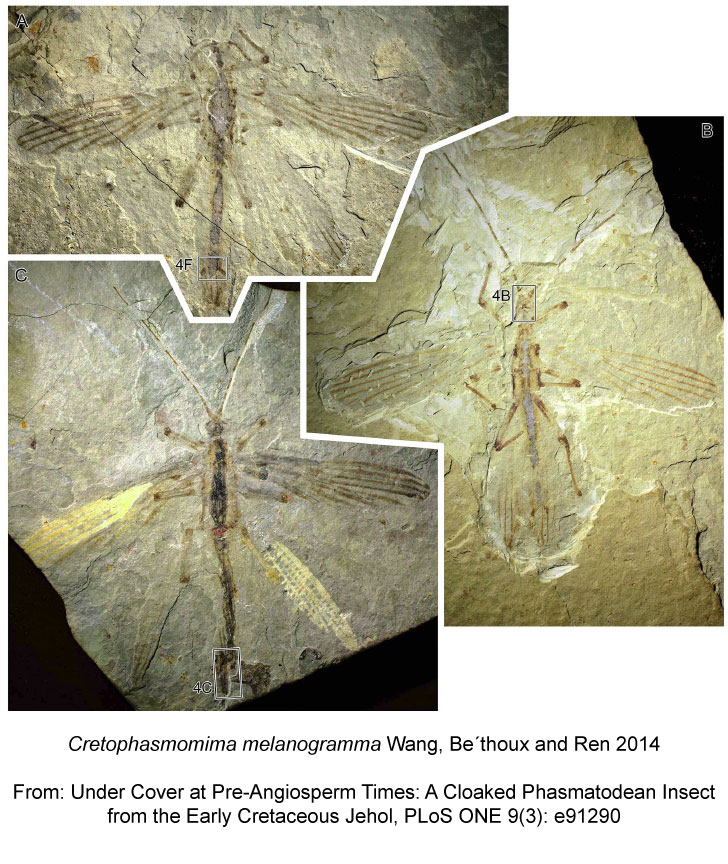

Of course, not all insects described today are still around to learn their names. This fossil walking stick, Cretophasmomima melanogramma, has been waiting to be discovered for roughly 126 million years!

Wang M, Be´thoux O, Bradler S, Jacques FMB, Cui Y, et al. (2014) Under Cover at Pre-Angiosperm Times: A Cloaked Phasmatodean Insect from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota. PLoS ONE 9(3): e91290. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0091290

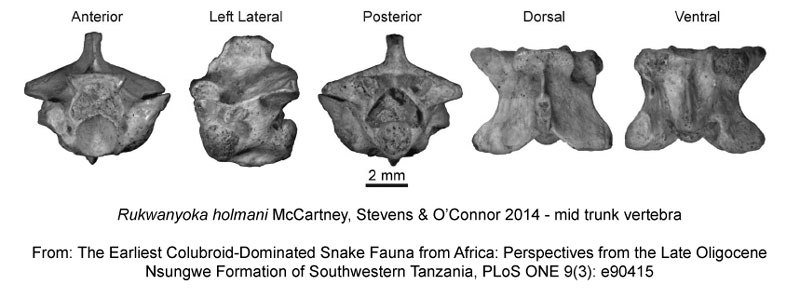

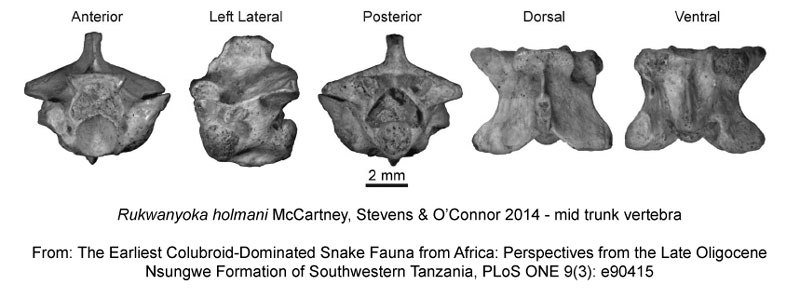

Continuing with fossils, Rukwanyoka holmani represents not only a new species of snake, but also a new genus, and is only known from a handful of vertebra.

McCartney JA, Stevens NJ, O’Connor PM (2014) The Earliest Colubroid-Dominated Snake Fauna from Africa: Perspectives from the Late Oligocene Nsungwe Formation of Southwestern Tanzania. PLoS ONE 9(3): e90415. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090415

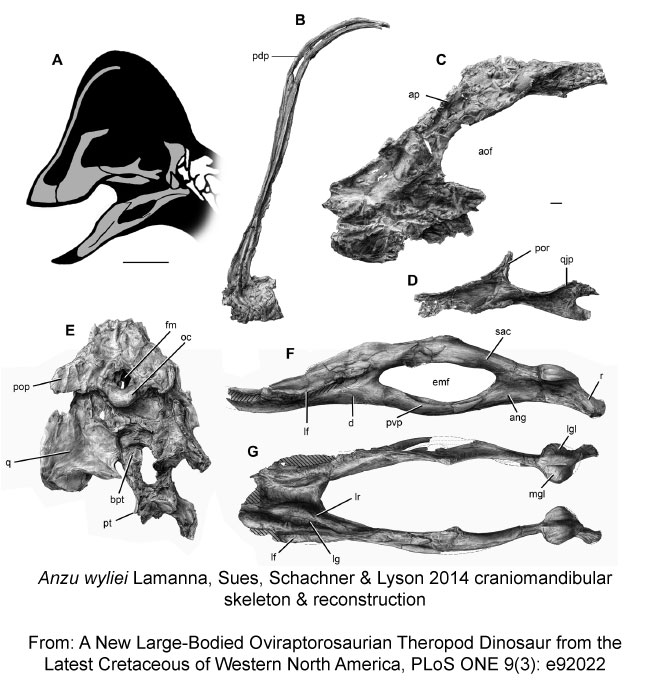

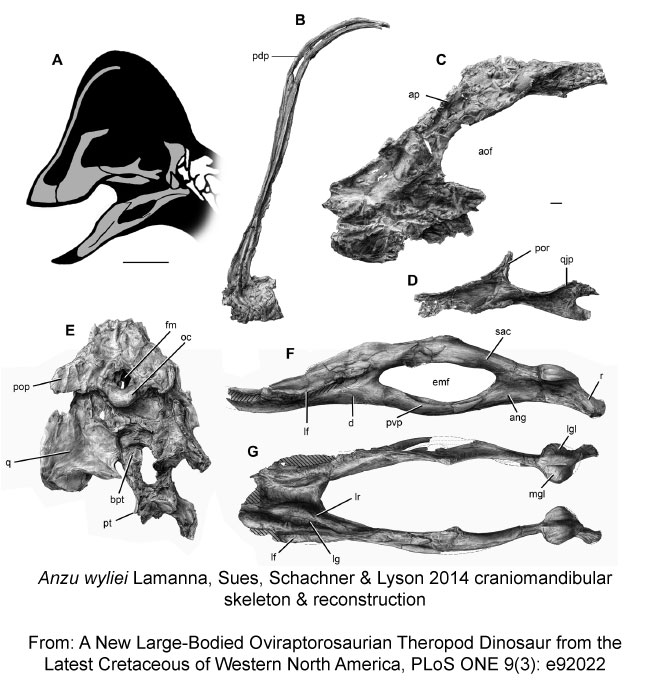

What would a story about new species be without a dinosaur? Making headlines as the “Chicken from Hell“, Anzu wyliei was an omnivorous bird-like dinosaur believed to have had feathered arms, which inspired the generic name: Anzu, a Mesopotamian feathered demon. The species epithet, wyliei, however, is in honour of Wylie J. Tuttle, the grandson of Carnegie Museum patrons! There’s no data provided whether young Wylie has the temperament or feathers of a Chicken from Hell, however.

Lamanna MC, Sues H-D, Schachner ER, Lyson TR (2014) A New Large-Bodied Oviraptorosaurian Theropod Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Western North America. PLoS ONE 9(3): e92022. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092022

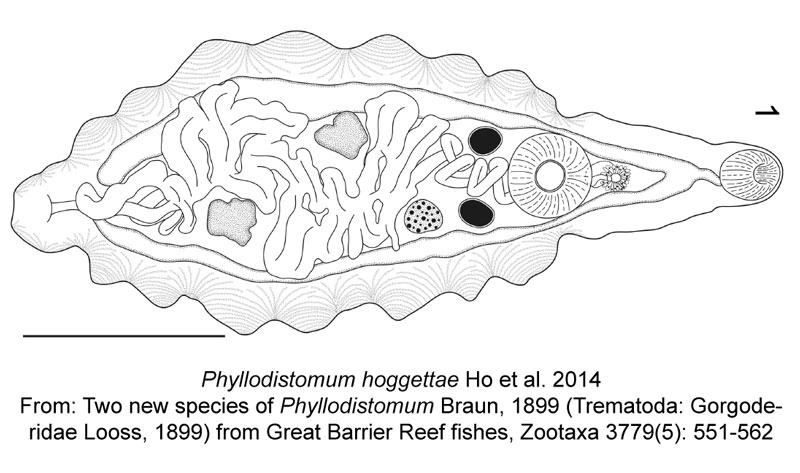

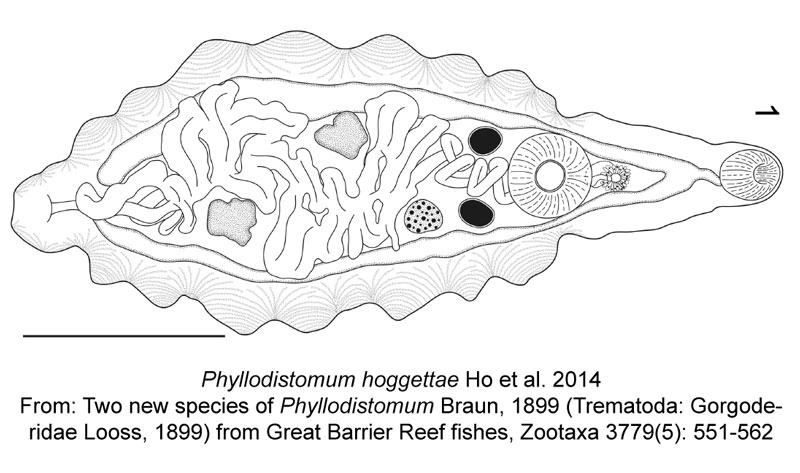

Finally, meet Phyllodistomum hoggettae, one of two parasitic trematode worms described today. This species is also named in someone’s honour, specifically Dr. Anne Hoggett, co-director of the Lizard Island Research Station, a research station within the Great Barrier Reef in Australia where the researchers conducted their work. Whie it may not be a dinosaur, it’s still an honour to have a species named after you, even if that species is a parasitic worm that lives in the urinary bladder of a grouper…

Ho, H.W., Bray, R.A., Cutmore, S.C., Ward, S. & Cribb, T.H. 2014. Two new species of Phyllodistomum Braun, 1899 (Trematoda: Gorgoderidae Looss, 1899) from Great Barrier Reef fishes. Zootaxa 3779(5): 551-562. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3779.5.5

—-

If you’re keeping track at home, that’s a total of 22 new animal species described in one day, which is actually below the daily average (~44 new species/day)! This isn’t including all the other things taxonomists work on, like identification keys, geographic records, phylogenetics, biogeography and the various other taxonomic housekeeping that needs to be constantly undertaken to ensure the classification of Earth’s biodiversity remains useful and up to date!

So the next time you look at an organism and are able to call it by name, take a moment to think about the taxonomist who worked out what that species is, gave it a name, and provided a means for you to correctly identify it, and perhaps check to see what new creatures are being identified each and every day!

—-

*- That I could find. I imagine there are more that were published in smaller circulation or specialized journals that I’m not aware of as well.