I was browsing Malcolm Campbell’s (highly recommended) weekly science link collection this morning, and came across an article in Nautilus on the newly described olinguito species. I was really enjoying the article, until the third to last paragraph, which triggered a bit of Twitter rant. Continue reading »

This morning, shark mega-enthusiast & PhD student David Shiffman (@WhySharksMatter) tweeted

I just uploaded a pic of me with a #Shark to Google Image reverse search and it IDENTIFIED THE SPECIES OF SHARK pic.twitter.com/fTpmHP7IVG

— David Shiffman (@WhySharksMatter) August 23, 2013

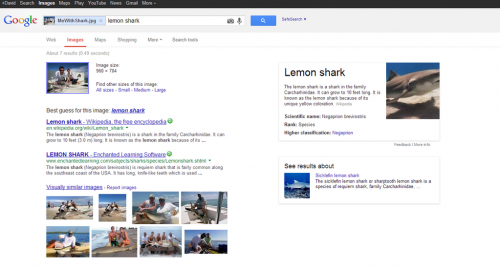

Here’s the screen cap image a little larger if you can’t make it out (click to embiggen further):

Is reverse Google Image search able to identify sharks to species? Yes, David included the search term “lemon shark” (David just let me know that Google included the text search terms itself… my mind is blown), but the fact that Google returned “Best guess for this image: lemon shark” might imply that they’re playing around with visual identification services, not just photo comparison. Considering how well reverse image search does at aggregating similar images, how many shark images are online & indexed by Google, and that many of those images are probably tagged with a species name nearby or in the metadata, I think the concept is entirely plausible.

Seeing how insect ID is kind of important to me, I tried it with a few of my insect photos, and got nothing. I even tried improving the odds by using search terms like David HAL 9000 Google did, and this is all I got:

I was beginning to get discouraged, but Marianne Alleyne (@Cotesia1) made a good point: perhaps it was the fact that David was sitting on the shark that mattered!

So, I reverse Google Image searched this photo

Apparently Google thinks this fly wrangler looks like a bride. Perhaps their search algorithm could use a little more work after all.

Clearly Google loves sharks and hates flies (and passenger pigeons). Not cool Google, not cool.

I guess we’ll just have to stick to other web-based tools for identifying flies for a little while longer. Darn.

Yesterday a new carnivorous mammal was described from Andean Ecuador (Bassaricyon neblina; the BBC has an excellent write up about it), and it’s been getting a lot of media attention. While I’m happy whenever the work of a taxonomist gets talked about, I have a suspicion that cute, fuzzy things get a greater proportion of that attention.

I pointed out on Twitter that while the one new mammal got international attention, 8 new skink species, 5 new sponges, 4 new water mites, a new fresh water shrimp, a new nematode and a new caddisfly, along with 8 new species of plants (and these were just the species published in Zootaxa & Phytotaxa) were described without much, if any, fan fare.

After my grumpy little observation, Rachel Graham (@PictureEcology) made an interesting suggestion:

@BioInFocus I completely agree with you, but it seems that new mammals are also much less frequently described.

— Rachel Graham (@PictureEcology) August 15, 2013

That got me thinking: is it our attraction to cute things that puts them in the news, or, thanks to more attention in the past and fewer species in total to be found, that describing a new mammal is so unusual that it’s newsworthy? So, I looked into it a little, did some back-of-the-napkin calculations, and tried to see why we seem to hear about some new organisms more than others.

Now, before I get into it, let me state that this is a very rough approximation of the taxonomic literature based on a few hours of quick searching, and I’m 100% confident that I’ve not found every relevant paper. This is just for fun, and should be taken with a pretty large grain boulder of salt. That being said, I think it’s suggestive of what’s happening, and at the very least might jump start some conversation. Also, this is only taking into account new, living (i.e. not fossil) species described in 2012, so beware small sample size distortion.

According to this Wikipedia list, there were 34 new species of mammals (Class Mammalia — ~5.5k described species) described in 2012 (the fact that there’s an updated list of newly described mammal taxa on Wikipedia would seem to lend credence to a Mammal Bias, but I digress): 16 bats, 9 rodents, 4 marsupials, 3 primates and 2 shrew-like things. Some of those, like Cercopithecus lomamiensis, got some media attention, while the others didn’t (I don’t recall hearing much excitement over the new bats, rats and shrews for example).

Now what if we look at other, less cuddly groups of organisms? Like sponges (Phylum Porifera — ~9k described species) for example. I found 54 new species of sponge described in 2012, which is a fairly similar ratio of new:known as mammals. I may be mistaken, but I can’t recall seeing a sponge on the home page of any news agencies (although the Lyre Sponge — Chondrocladia lyra — was selected by ASU as one of the Top 10 New Species of 2012).

Same story with harvestmen (Order Opiliones — ~6.5k described species): I located 46 new species for 2012, which is a few more than the mammals, but I kind of doubt there were reporters knocking on arachnidologist’s doors inquiring about them.

Finally, let’s look at rotifers (Phylum Rotifera — ~2.2k described species), those neat little creatures that whirl around in pond water. In 2012, as far as I can tell, only 1 new species was described. One. As far as rarity of discovery goes, it doesn’t get much more unusual than that, and I think it’s safe to assume no one heard about Paraseison kisfaludyi, even though it sounds pretty interesting (it’s only the fourth species described in it’s Order, and it lives INSIDE the carapace of a tiny crustacean — seriously cool).

I think we can safely say that while mammals may indeed be infrequently described, that’s not the reason they make the news, and that we’re all saps for those large eyes and furry bodies that remind us of Rover, Kitty, and ultimately, ourselves.

So, is there a distinct Mammal Bias in the news media? Probably. Is that a bad thing? Maybe not. While it’d be nice to see some of the other new & fascinating creatures being described by the world’s taxonomists be spotlighted, as long as people are reminded we still don’t know our neighbours very well, and that there are a lot of dedicated people out there working hard to introduce them to us, then I think we’re making progress.

It’s not like newly described invertebrates don’t make the news cycle (a couple of recently described dance flies were getting some attention earlier in the week thanks to some good-spirited nomenclature), it’s just that there’s a whole world of interesting biology and taxonomy waiting to be told outside of the cuddly stuff. All you need to do is look.

—————

Quick footnote with an anecdote: the number of people involved in the description of a new mammal species heavily outweighs the number of people involved with the invertebrate groups I looked at. For the 34 mammal species described in 2012, 107 people were listed as authors on the papers (3.14 people/new species); Opiliones – 26 authors for 46 species (0.57 people/new species); rotifers – 2 authors for 1 species; and sponges – ~35 authors (I lost count) for 54 species (~0.65 people/new species). I’m not really sure what this means (if anything) other than we could really use more taxonomists working on invertebrates, but I thought it was interesting.

The Bug Chicks (aka Jessica Honaker & Kristie Reddick) are two of the most enthusiastic, creative and hilarious entomologists I’ve ever had the good fortune to meet. They’ve dedicated their careers to educating people (especially kids) about insects and related arthropods through interactive workshops and field camps, as well as with a whole series of videos showing the weird, wacky and wonderful ways in which insects go about their lives, and why they’re important in ours (their earwig video is probably my favourite, I highly recommend checking it out).

The Bug Chicks have done an amazing job on their own so far, but they want to reach an even larger audience and are gearing up for an epic cross-country road trip/web-series to show off some of the incredible insects that can be found in our own backyards. Check out the promo trailer:

Honda is lending them a brand new van and Project Noah (a web & mobile natural history app supported by National Geographic) is making sure all the cool stuff they find is accessible to viewers around the world, but Jess & Kristie still need some help from you to make their dream a reality. They’ve set up an Indiegogo crowd-funding campaign to help raise the money they need to haul that crazy couch from the forests of Oregon to the deserts of Arizona, and from the mountains of Yellowstone National Park to the beaches of Assateague State Park in Maryland. They’ve got some great perks for those that donate, ranging from “Bug Dork” bumper stickers and insect artwork to classroom lectures for your favourite student!

At a time when science programming on network and cable TV has been replaced with fauxumentaries and fear-mongering reality shows, we NEED people like The Bug Chicks to help inspire and educate future generations of scientists, biologists, and entomologists. Jess & Kristie are two of the finest role models you could ever want, and I fully believe that they have the potential to change the landscape of educational video programming with their work!

So if you can, check for change under your couch cushions, donate a few dollars (or as much as you can afford) and help spread the word by telling your friends and neighbours! There’s only 9 days left in their campaign, and while they have a long ways to go to reach their goal, every dollar will help them bring quality educational entertainment to you and the rest of the world.

Donate to their Indiegogo Campaign HERE.

Finally, we talked to The Bug Chicks about their campaign recently on Breaking Bio, where they announced their partnership with Honda, and explain what they hope to do on their trip, give some hints about some of the cool stuff they’re hoping to find, and share why it’s important for there to be strong, women role models online and in the real world.

Evolutionary biology is dramatic. Species come, and species go. Simple, random mutations allow organisms to exploit bold new resources. A year’s worth of field data can hinge on the immediate availability of duct tape. You get the idea.

After discussing these thoughts on Twitter with @Sciencegurlz0, @sciliz & @cbahlai this evening, we’ve come up with a way of conveying the events occurring in research labs and backyards around the world in a manner befitting their seriousness: a YouTube series featuring abstracts of evolutionary biology papers being read dramatically by professional actors.

Picture it: Hugh Jackman belting out the abstract for “Macrophages are required for adult salamander limb regeneration“, or Jenny McCarthy sharing her talents to pass along the “Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2009, Featuring the Burden and Trends in Human Papillomavirus (HPV)–Associated Cancers and HPV Vaccination Coverage Levels“, or Sir Patrick Stewart providing a dramatic reading of, well, anything really (although I’d suggest “Space travel directly induces skeletal muscle atrophy“). Yes, I believe this is what the internet was made for.

While the videos would be highly entertaining and have the potential to go viral, I’d accompany them with explanatory write ups of the paper in question. The silly-sounding readings would serve as the hook to pique people’s interest in the science (i.e. what on earth is Hugh Jackman singing about), and encourage them to read more about the paper with the help of a skillful synopsis provided by one of the many talented science writers currently at work on the web.

While I think the idea has a lot of potential, we don’t have the connections to make it a reality (I’m not sure I know any actors personally, famous or otherwise). So, I’m throwing the idea out into the web with the hopes that a connected and creative person out there will run with it. The online science community is a large and diverse place, and I’m sure there’s someone who can make this a reality.

The only thing I ask is that you send me a link when you roll it out, because I’d really love to watch Samuel L. Jackson ad lib “Germs on a Plane: Aircraft, International Travel, and the Global Spread of Disease“.

In what will probably be the only blog post I ever write about plant taxonomy, I bring you one of the greatest natural history papers ever published:

Cneoridium dumosum (Nuttall) Hooker F. Collected March 26, 1960, at an Elevation of about 1450 Meters on Cerro Quemazón, 15 Miles South of Bahía de Los Angeles, Baja California, México, Apparently for a Southeastward Range Extension of Some 140 Miles

R. Moran, 1962 (Madroño, 16)

Yes, that’s the full title of the paper. The introduction/methods/results/discussion reads as follows:

I got it there then (8068).

which is then followed by almost a full page of hilariously detailed acknowledgements thanking everyone who had a hand in this rigorous scientific study. You can read the full work in all it’s glory here.

In case you were curious, Cneoridium dumosum (or bushrue as it’s commonly known) is a species of flowering citrus shrub known from southern California and, thanks to Dr. Moran’s dedication to publishing his findings, northern Mexico.

Cneodidium dumosum flowers, which in this humble entomologists opinion, are fully deserving of such an awesome place in the history of the taxonomic literature. Photo by Stickpen, public domain.

I can’t help but wonder how a journal would react should you try something like this today; would they have the good nature to publish it, or is this an auto-reject-in-waiting?

Thanks to Chris MacQuarrie for his photographic memory archiving the entire discussion section of this paper and bringing it to my attention, and Rafael Maia for helping to get me a copy of the full text. My sincerest apologies to Rafael’s lab mates for his subsequent & uncontrollable laughter.

UPDATE (July 12, 2013): After George Sims inquired about the “(8068)” in the comments below, I turned to Twitter to crowd source the answer, and sure enough, got an answer! Tyler Smith (@sedgeboy), a botanist at Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada in Ottawa, hypothesized the number was the author’s collection number for the specimen, and then proved his point by finding specimen #8071 in the Missouri Botanical Garden’s database, which was collected on the same day and at the same location! Why Dr. Moran didn’t include this with the rest of the collection data in the title of the note is a bit odd, but as nothing else about this note is “normal”, I suppose anything goes!

Also, David Shorthouse (@dpsSpiders) found Dr. Moran’s obituary, which provides an interesting overview of the life of a legendary naturalist and field biologist.

————

Moran R. (1962). Cneoridium dumosum (Nuttall) Hooker F. Collected March 26, 1960, at an Elevation of about 1450 Meters on Cerro Quemazón, 15 Miles South of Bahía de Los Angeles, Baja California, México, Apparently for a Southeastward Range Extension of Some 140 Miles, Madroño, 16 272-272.

Hey blog, what’s new? Oh, that’s right, nothing lately… My bad. To say the past few months have been hectic would be a bit of an understatement, but that’s a tale for another time. To kickstart my bloggy brain cells, I figured I’d ease back into it with a Tuesday Tune, then maybe a new photo, and quite possibly a rage-driven rant observation on society later this week. Fun!

Normally with Tuesday Tunes we get a song that may have insects in the title, the lyrics, or maybe a cameo in a video. This week’s song not only features a great title & lyrics, plus a psychedelic & morphologically awesome video, but also some killer album art!

Meet Mosquito by indie rockers Yeah Yeah Yeahs (be sure to watch to the end) –

If you thought natural selection would punish a hyper-obvious mosquito like the one in the video, you’d normally be correct. However, the psychedelic Psorophora ferox would beg to differ!

Psorophora ferox demonstrating that art isn’t always crazier than nature! Photo by Kathleen Chute

Thanks to Dr. Cameron Webb (@Mozziebites) for alerting me to this song when it came out earlier this spring!

———-

This song is available on iTunes: Mosquito – Mosquito (Deluxe Version) by Yeah Yeah Yeahs

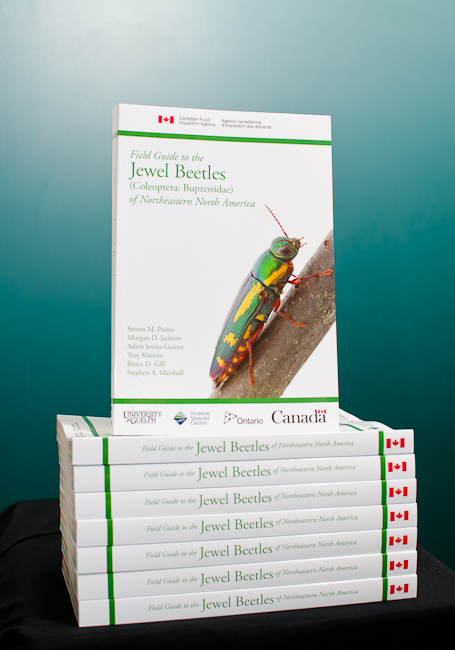

Good news! Field Guide to the Jewel Beetles of Northeastern North America is finally shipping! If you pre-ordered a copy of the book and you live in Canada, you should be receiving the book any day now (if you haven’t already). If you don’t live in Canada, don’t worry, we haven’t forgotten about you. To make sure that all Canadian orders are filled (including those in forestry research departments and industry), international shipments are being held back a couple of weeks, but should begin shipping by early June.

On Mother’s Day, many men pick up flowers or make breakfast in bed for their partners to show their appreciation for everything moms do. If you’re a taxonomist, you can go a step further and give the eternal gift of patronymy (or perhaps matronymy?) by naming a new species after the mother of your offspring!

In a recent Zootaxa paper, that’s exactly what Heron Huerta did, naming a new species of Mexican Scatopsidae Colobostema marielae, and earning extra brownie points in the etymology:

This new species is named after my wife, Mariela Trujillo De la Cruz, for her unconditional support, love and enthusiasm for my projects.

– Huerta, 2013

Scatopsidae are commonly referred to as minute black scavenger flies (or even less romantically, dung midges), and with larval habitats ranging from the decaying to the defecated, having something like this named for you may seem less like an honour and more like a thinly veiled insult. But when you consider your fly is 1 of only ~250 species known, that your fly’s relatives are found literally around the world and have been helping keep us out of the rot since the time of T. rex, and that, while not as flashy or well known as other organisms, someone has devoted their life to learning all there is to know about your fly and has decided that you are so important you should be forever immortalized as the namesake for this unique being, well, that’s a pretty powerful gift.

Happy Mother’s Day.

A Colobostema species from Alabama. Colobostema mariela apparently looks much like this, but with a uniquely constricted tergite 7 (you’ll just have to take Heron’s word on this one). Photo by Robert Lord Zimlich, used under CC BY-ND-NC 1.0 licence.

——–

Nominate this species for New Species of the Year!

HUERTA H. (2013). New species of the genus Colobostema Enderlein (Diptera: Scatopsidae) from Mexico, Zootaxa, 3619 (2) DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3619.2.6

The east coast is about to get a little more crowded, and whole lot louder, as Brood II of the 17-year cicada (which is actually a synchronized cohort of three different species: Magicicada septendecim, Magicicada cassini, & Magicicada septendecula) prepares to make its first appearance since 1996.

Conceived, laid and hatched while the Macarena was sweeping the globe, Brood II has since been biding it’s time underground in nymphal form, feeding off sap stolen from the roots of trees and counting down the years until it was time to make their grand appearance. But how DO they count down the years? 17 years is an incredibly long time, especially when you live more than a foot underground, insulated from traditional stimuli like photoperiod and temperature.

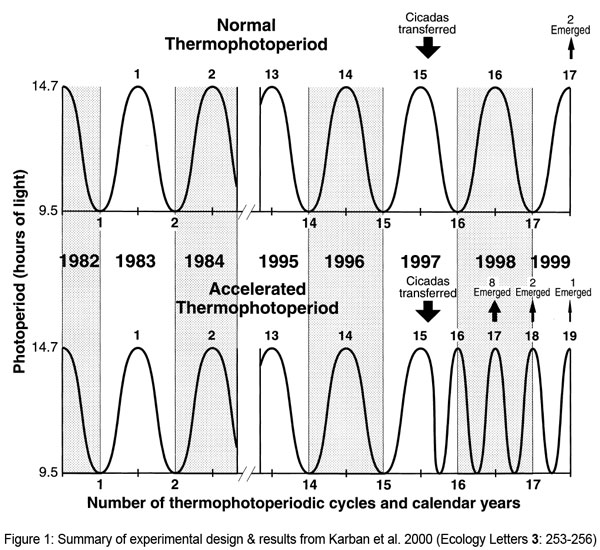

Richard Karban, who wrote that he’s dreamed of tricking periodical cicadas into emerging early for most of his adult life, had an idea, and designed an elegant experiment to see if he could confuse his cicadas by accelerating the life cycle of the trees they were dependent on.

Rather than making a poor graduate student sit and wait 17 years for a cicada to emerge, Karban dug up and transplanted 15-year old Brood V nymphs from Pennsylvania onto potted peach trees in his University of California, Davis lab, a difficult procedure that involves potatoes and a cross-country road trip with some unusual company, and which had failed the 3 previous times it was attempted. This time however, Karban successfully managed to transplant 13 nymphs, with 11 surviving on his accelerated-cycle trees which underwent 2 flowering cycles per year (bud-> leaf-> flower-> leaf drop-> dormancy-> bud-> leaf-> flower-> fruit-> leaf drop), and 2 surviving on his control trees which only underwent a single cycle per year (bud-> leaf-> flower-> fruit-> leaf drop-> dormancy).

Back in the wilds of Pennsylvania and on the control trees, Brood V adults were expected to emerge in the spring of 1999, which is exactly what they did. However, the ones who were feeding on the accelerated-cycle trees got the party started a full year early, with 8 of the 11 individuals emerging right when Karban hypothesized they would: spring 1998!

Karban realized his dream, having successfully fooled a few periodical cicadas into emerging early, and in the process showed that cicadas are able to count the seasonal cycles (or phenology) of their host trees to keep track of time rather than relying on other direct stimuli. The exact mechanism by which cicadas keep track of how many cycles have passed is still not well understood, although it’s probably safe to assume that the cyclic availability of tree sap & nutrients influences the development of the nymphs in some way. The fact that there are still such large pieces of the phenomenon still waiting to be understood is just as exciting as the prospect of millions of brightly coloured bugs emerging en masse to serenade you this summer.

So, if you happen to find yourself on the East Coast in the coming weeks, stop and take the opportunity to listen to a symphony 17 years in the making. And if you notice a subtle-but-catchy Latin beat to the buzz of periodical cicadas, just be glad it’ll only last a couple of weeks; those poor cicadas have been humming the Macarena to themselves for the past 17 years!

Photograph by C. Simon. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000892.g003. Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 License.

————-

Karban R., Black C.A. & Weinbaum S.A. (2000). How 17-year cicadas keep track of time, Ecology Letters, 3 (4) 253-256. DOI: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2000.00164.x