The extreme cold snap encompassing a large portion of continental North America (termed a Polar Vortex, which you can learn more about via NPR and Quartz) has made it dangerous to remain outside for long, even when bundled up in more layers than a Thanksgiving turducken. While we can rely on our technological ingenuity to find solutions to this chilling problem, what about our insect neighbours who have been left out in the cold?

Eurosta solidaginis has a warning for you.

Most insects seek shelter in the fall before temperatures begin to dip, either laying their eggs in sheltered locations, or hiding out as larvae, pupae or adults in the comparative warmths of the leaf litter, deep within trees, or even taking advantage of our warm hospitality and rooming with us in the nooks & crannies of our homes. But what about species like the Goldenrod Gall Fly (Eurosta solidaginis) which are literally left hanging out in the middle of nowhere and completely at the mercy of Jack Frost?

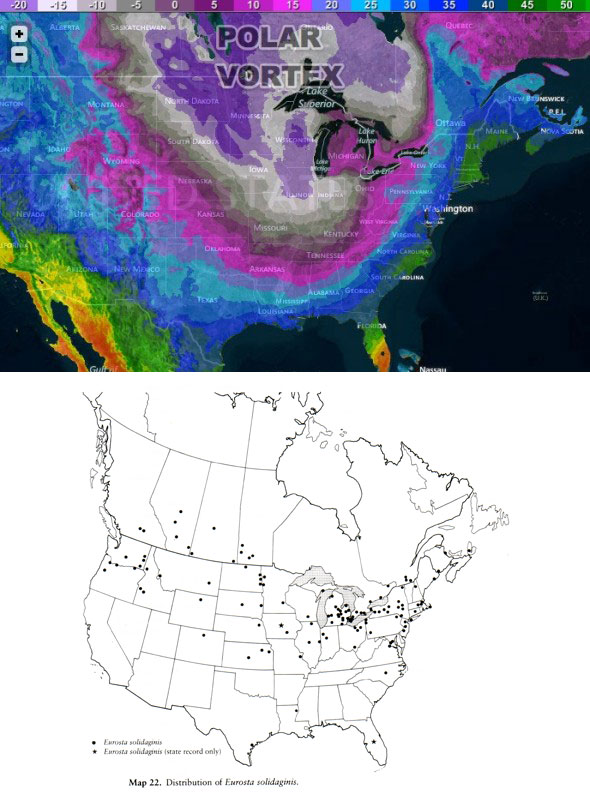

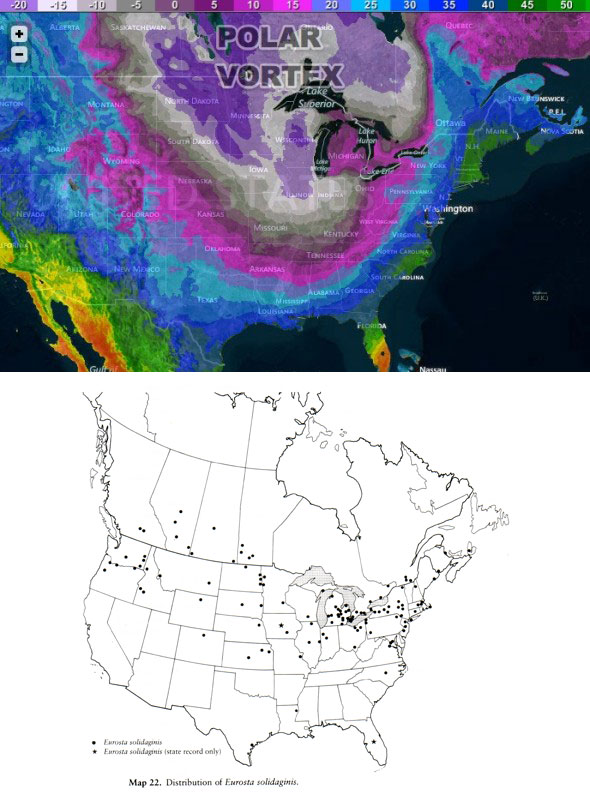

Polar Vortex vs. Goldenrod Gall Fly. Polar Vortex map courtesy of RightWeather.com, Eurosta solidaginis range map from Foote et al. 1993

If you live in eastern North America, you’re probably familiar with the Goldenrod Gall Fly, even if you don’t realize it. This fruit fly — the ripe fruit kind (family Tephritidae), not the rotting banana kind (family Drosophilidae) — is one of the more ubiquitous insects, and is found pretty well anywhere goldenrod grows, including in urban environments like parks & abandoned lots. Adults are weak fliers and aren’t often seen unless you’re actively looking for them, but in this case, it’s the larvae that you’ve likely seen a hundred times — rather, you’ve likely seen their makeshift homes a hundred times. The larvae of this species live within the stem of goldenrod plants (Solidago spp.), and trick the plant into growing a big spherical nursery for the fly maggot to live & feed in (technically called a ‘gall’), and which stands out like the New Year’s Eve ball in Times Square, albeit without the mirrors and spotlights of course.

Goldenrod Gall Fly galls in Guelph, Ontario

While these galls provide a modicum of protection from predators and parasitoids (although some still find a way), they don’t provide much, if any, insulation from the elements, meaning that the larvae must be able to survive the same air and windchill temperatures that we do. To do so, Goldenrod Gall Fly larvae are not only able to safely freeze without their cells being torn apart by tiny ice daggers by partially drying themselves out, but they also change the temperature their tissues freeze at by manufacturing anti-freeze-like chemicals. Together, these cold-tolerance strategies allow the maggots to survive temperatures as low as -50°C (-58°F)! Just take a moment to consider what it would feel like to stand outside almost anywhere in central North America on a day like today wrapped in only a few layers of tissue paper; BRRRRRRR!

All that stands between a Goldenrod Gall Fly maggot & the extreme cold is a few centimeters of dried plant tissue. (The maggot is the little ball of goo in the bottom half of the gall)

For us, the multiple warm layers of clothing we bundle up in on days like today allow us to survive and eventually have children, thus passing our genes along, despite living in a habitat that is occasionally unfit for human life. It would stand to reason then that other organisms would also enjoy the same benefits and evolutionary advantage from thermal insulation, but, for the Goldenrod Gall Fly at least, the complete opposite is true! Goldenrod isn’t exactly the most robust structure, and it doesn’t take much effort from the wind, passing animals like people or dogs, or other not-so-freak phenomena to knock goldenrod stems over, allowing galls to be buried in snow and protected from the harshest temperatures (snow is an excellent insulator, and temperatures in the snowbank generally hover around 0°C (32°F)). This would intuitively seem like a good place to be if you were fly maggot, out of the daily temperature fluctuations and extreme cold and in a more stable environment. However it turns out that individuals that mature in galls on the ground and covered with snow are at a significant disadvantage evolutionarily speaking, with grounded females producing 18% fewer eggs than females who grew up fully exposed to the elements (Irwin & Lee, 2003)!

This Goldenrod Gall Fly, while warm(er), will likely produce fewer offspring when it emerges (assuming it’s a female).

Why might that be? Well, let’s think about it for a moment. If you’re a fly maggot hanging out above the snow when it’s -20°C, you’re likely going to be frozen solid and in a cold-induced stasis, not doing much of anything, even at the cellular level. But, if you’re as snug as a ‘bug’ under the snow at ~0°C, your body won’t be frozen, and thus you’ll be forced to carry on with day-to-day maintenance & cellular functions like breathing, waste removal, etc, even if only minimally. When you live in a closed system like a hollowed-out stem gall on a dead plant without any food, any energy you spend on daily functions as a “teenager” putting in time under the snow all winter long means you’ll have less energy you can put towards making eggs as an adult. If you’re a Goldenrod Gall Fly maggot, it pays to be left out in the cold!

—

Foote, R.H, Blanc, F.L., Norrbom, A.L. (1993). Handbook of the Fruit Flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) of America North of Mexico. Comstock Publishing Associates, Ithaca NY. 571pp.

Irwin J.T. & Lee, Jr R.E. (2003). Cold winter microenvironments conserve energy and improve overwintering survival and potential fecundity of the goldenrod gall fly, Eurosta solidaginis, Oikos, 100 (1) 71-78. DOI: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.11738.x

—

Some additional thoughts: You’d think that a nearly 20% difference in egg production would create significant evolutionary pressure for Goldenrod Gall Fly females to select the strongest, least-likely-to-break-and-fall-over goldenrod stems. It’s possible that the randomness of goldenrod stem breakage negates any evolution of host plant selection, but I would tend to doubt it. I did a quick Google Scholar search to check whether anyone had examined this in greater detail, but I didn’t see anything. Perhaps an avenue of future study for an evolutionary biology lab out there?