Oh give me a home where the buffalo roam,

Where the deer and the antelope play,

Where seldom is heard a discouraging word,

And the skies are not cloudy all day.

When it comes to evocative imagery of North American landscapes, perhaps no other song brings nature to life like Home on the Range. Sung round a campfire, your imagination can’t help but picture the Great American Plains teeming with life and big game under wide open skies as far as the eye can see. Yet, even as Dr. Brewster Higley was writing Home on the Range in 1876, the ecosystem that inspired him was already being drastically altered, and within a decade only a few hundred buffalo would roam where millions had previously.

And while buffalo, or more properly, bison, have largely been extirpated from their home on the range, they left behind an ecological footprint, if not hoofprints, that may influence the ways in which the deer and the antelope, but also the sheep, play.

When we think of animal engineers, we normally think of the beaver, reshaping waterways with dams and lodges carefully crafted with no regard for canoeists or property owners. But bison are known to wallow in their own environmental ingenuity as well, quite literally. Buffalo wallows are depressions in the plains that after decades of communal use by bison herds develop a layer of water-impermeable soil that helps trap water and mud near the surface, which in turn draws more and more wildlife to them during the hot, dry, summer months. These communal baths are even visible from space, and have stuck around for centuries even where bison no longer visit.

By rolling around and washing off all manner of biological material, from skin and hair to dust and plant matter, along with all manner of bodily fluids (bison aren’t adverse to peeing in the pool, so to speak), these wallows, when used, become highly enriched with organic matter. And where there are pools of organically-rich, wet, mud, there are undoubtedly a range of flies just waiting to make themselves at home.

Enter new research by Robert Pfannenstiel and Mark Ruder of the Arthropod-Borne Animal Diseases Research Unit of the USDA in Kansas. Pfannenstiel and Ruder wondered whether biting midge larvae (Ceratopogonidae) in the genus Culicoides were more likely to be found in wallows that haven’t been used for generations but which still collected water, or in wallows that rebounding bison have adopted and infused with fresh fertilizer.

When it comes to aquatic fly larvae associated with “Arthropod-Borne Animal Diseases”, Culicoides may not seem an obvious choice, with things like mosquitoes and black flies more often drawing our attention. But just as the megafauna of the Great Plains has changed since 1876, so too has its microfauna.

In the late 1940’s, a new disease began to emerge in the sheep and cattle of the Southwest, first in Texas, and then California. Termed “soremuzzle” by ranchers and shepherds, infected livestock, particularly sheep, would develop swelling and ulcers in and around their nose and mouth, become fevered, pull up lame, and in some extreme cases, the animal’s hooves would fall right off. Then, in 1952, immunologists finally put the pieces together and realized “soremuzzle” was actually Bluetongue Virus (BTV), a vector-borne disease only known from Africa and the Mediterranean at the time. Since then, Bluetongue Virus has spread from the American Southwest up throughout the plains and has begun creeping into the Midwest, as well as spreading to all the other sheep-inhabited continents, recently becoming a major concern for shepherds in the UK.

The wide spread of BTV was made possible in part by ranchers shipping infected sheep (which commonly don’t show signs of infection, and can remain infectious for weeks following initial exposure) around the globe, but also by the close relationships among the virus’ vectors, biting midges in the genus Culicoides. In the Mediterranean, the only vector had been Culicoides imicola, but eventually enough infected livestock spread into the neighbouring ranges of Culicoides obsoletus and C. pulicaris in Europe, who then helped spread the disease all across the continent.

Meanwhile, in North America, another pair of Culicoides species with wide ranges of their own found themselves home to BTV, Culicoides sonorensis, and Culicoides insignis, bringing us back to buffalo wallows and muddy waters.

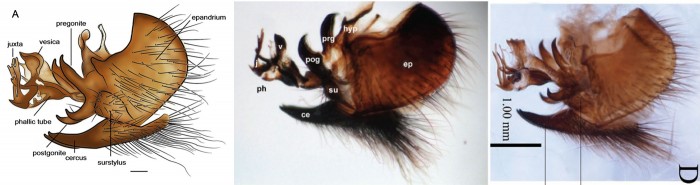

Culicoides sonorensis – Photo copyright Adam Jewiss-Gaines, used with permission.

Pfannenstiel and Ruder scooped mud from buffalo wallows in and around the Konza Prairie Biological Station in Kansas (where, incidentally, the state song just so happens to be Home on the Range), some of which were currently being used by bison, and some of which had not been visited by bison for years, and reared the Culicoides larvae from each sample in the lab. They found that active bison wallows were home to Culicoides sonorensis (as well as several other closely related Culicoides species), with several dozen specimens reared from mud collected throughout the summer, while relict wallows were not.

All of this leads to an extremely complex conservation conundrum. By bringing back bison, and allowing them to resume wallowing in their wallows, it seems we’re increasing habitat for a fly species that carries a disease not present the last time bison roamed the range. Bison themselves are susceptible to BTV, but like cattle, don’t normally show the extreme symptoms or mortality that sheep do. However, the bison’s range is also home to nearly half of America’s sheep, with more than 2 million heads grazing the same areas as bison once roamed. More bison may equal more Culicoides, which in turn could equal more cases of BTV among livestock, a prospect that likely won’t sit well with ranchers and shepherds in the area.

What’s more, sheep aren’t even the most susceptible plains animals to BTV. While most infected sheep may show clinical signs of BTV infection, usually less than 30% of infected animals actually succumb to the disease. Meanwhile, the deer and the antelope (pronghorn) playing alongside the wallowing bison and grazing livestock experience an 80-90% mortality rate when infected with BTV, and will likely serve to spread the disease further, faster.

Of course, being a vector-borne disease, BTV can only spread as far as its vector is found, and unfortunately, we’ve been caught a little unprepared to answer just how far that may be. Culicoides are difficult to identify, and so we don’t know where these flies may or may not be found currently, and more importantly, where they may spread to in the future as climate change broadens acceptable habitat. Luckily, researchers like Adam Jewiss-Gaines, a PhD student at Brock University, are working to not only figure out where Culicoides‘ are found, but are also developing keys and resources that will allow others to track the great migration of these tiny flies.

Conservation biology is complicated, and fraught with trade-offs, especially when we try to conserve species in landscapes on which we place a high economic value and which we have changed immutably. So while we’ve brought bison from the brink of extinction back to Home on the Range-era levels, we now find ourselves presented with a new range of conservation challenges, and there may yet be dark clouds in our future skies.

—-

Pfannenstiel, R. S., and M. G. Ruder. 2015. Colonization of bison (Bison bison) wallows in a tallgrass prairie by Culicoides spp (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). J. Vector Ecol. 40: 187–90.