On the island of Raivavae, one of the Austral Islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, buried deep beneath the surface of a swamp in mud accumulated at the foot of a stream for thousands of years, scientists have found all that remains of a unique new species of Black Fly (Simuliidae): larval head cases left behind when the flies molted into pupae. These subfossils, not yet hard and mineralized like conventional fossils yet still preserved in near-perfect condition by the mud, not only raise the question of how a tiny little fly found its way to an island in the middle of nowhere, but also provide the only evidence of a murder mystery 2 million years in the making.

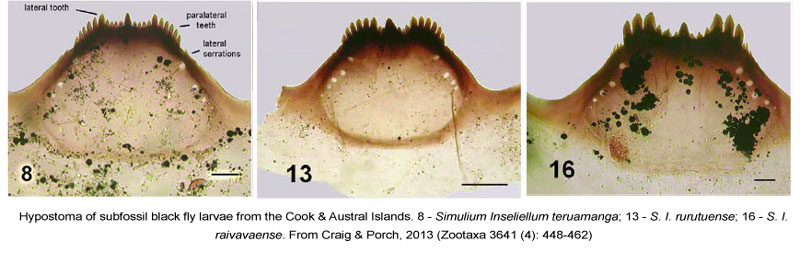

The missing species on Raivavae is Simulium Inseliellum raivavaense, recently described by Douglas Craig of the University of Alberta and Nick Porch of Deakin University in Australia, from material collected in 2010. Despite the subfossil larval head capsules being the only “specimens”, Craig & Porch were able to determine S. I. raivavaense was a new species based on the shape, position, and number of teeth on the hypostoma, essentially the lower lip of a black fly larva’s mouth.

Let’s back up a few million years, and start this story at the beginning. The Cook and Austral Islands are a chain of volcanic landmasses more than 3,000 km northeast of New Zealand that began forming roughly 20 million years ago (mya). The oldest island in the archipelago is Mangaia, which was formed 19mya but remained underwater until relatively recently, while the youngest is Rarotonga, which formed roughly 2mya and which broke above sea-level right away. It probably wasn’t long after Rarotonga appeared that plants and animals were blown by the wind or carried on the seas or migratory birds and began to colonize the virgin landscape. Of immediate importance to black flies was that Rarotonga is relatively large (67 km2) and currently stretches more than 650 metres above sea-level at its highest point, both factors that enable cloud formation and consistent precipitation, creating fresh water streams black fly larvae depend on. The first black flies to colonize the Cook Islands likely flew there with the assistance of the wind, probably from one of the other archipelagos to the west, and probably not long after Rarotonga was formed. Think of it like hitting a bulls-eye with an arrow from hundreds, if not thousands, of kilometers away by accident, without knowing there was even a target in the distance to aim at. This is Island Biogeography, a fascinating field of study combining geology with evolution which was pioneered by E.O. Wilson and Robert MacArthur in the 1960’s.

Let’s back up a few million years, and start this story at the beginning. The Cook and Austral Islands are a chain of volcanic landmasses more than 3,000 km northeast of New Zealand that began forming roughly 20 million years ago (mya). The oldest island in the archipelago is Mangaia, which was formed 19mya but remained underwater until relatively recently, while the youngest is Rarotonga, which formed roughly 2mya and which broke above sea-level right away. It probably wasn’t long after Rarotonga appeared that plants and animals were blown by the wind or carried on the seas or migratory birds and began to colonize the virgin landscape. Of immediate importance to black flies was that Rarotonga is relatively large (67 km2) and currently stretches more than 650 metres above sea-level at its highest point, both factors that enable cloud formation and consistent precipitation, creating fresh water streams black fly larvae depend on. The first black flies to colonize the Cook Islands likely flew there with the assistance of the wind, probably from one of the other archipelagos to the west, and probably not long after Rarotonga was formed. Think of it like hitting a bulls-eye with an arrow from hundreds, if not thousands, of kilometers away by accident, without knowing there was even a target in the distance to aim at. This is Island Biogeography, a fascinating field of study combining geology with evolution which was pioneered by E.O. Wilson and Robert MacArthur in the 1960’s.

Craig & Porch have now begun tracing how black flies island-hopped their way down to Raivavae.

Here you can see the islands in the Cook & Austral Islands on which black flies have been recorded. The dark blue marker is Rarotonga, the island thought to have been the first island in the area colonized by black flies. Shortly after establishing here, Craig & Porch believe a population of adult black flies was swept all the way to Tubuai (pale green marker), where they secured a foothold in a stream, and from there a population then migrated to Raivavae (red marker). All three of these vicariance events were believed to have happened within the first million years after black flies made it to Rarotonga, primarily because each of these islands is home to individuals with different larval morphology, representing speciation events. In the million years prior to today, Craig & Porch suggest that flies from Tubuai (pale green) became established on Rurutu (dark green) after it rose above sea-level (which happened ~1.1mya — it had been an underwater coral atoll for the first 11 million years of its existance), but which didn’t leave enough time for the flies to develop any significant changes in their morphology. The flies on Tubuai & Rurutu (green markers) are both considered to be Simulium I. rurutuense today. Similarly, sometime in the past 35,000 years, the islands of Atiu and Mangaia (light & medium blue respectively) were pushed above sea-level as Rarotonga continued to grow from its volcanic base, meaning Simulium I. teruamanga was only able to spread to these islands recently.

So far, black flies have yet to be found on the island of Rimatara (the central black marker), likely because the island doesn’t have a high enough peak to ensure a constant supply of running water. The other black marker is Rapa-iti, an island on which the habitat appears to be suitable for black flies, and yet there is no evidence that they’ve ever been present there. It would seem that as far as black flies are concerned, this is one target they’ve been unable to hit.

By combining evolution & geology, Craig & Porch have explained how black flies colonized these remote Pacific islands, leaving us with the curious question of why there are no black flies alive on Atiu, Tubuai or Raivavae today, despite subfossil evidence indicating they had lived on each of these islands up until very recently.

Black flies, seeds and birds are of course not the only creatures that ride the wind and the waves to new islands; humans are notorious for doing it as well. In fact, we’re so good at finding new land and making it home that ancient Polynesians spread all the way across the Pacific from southern Asia in less than 4,000 years, arriving in the Cook and Austral Islands sometime prior to 1300 AD.

By taking core samples deep into the mud of the islands, Craig & Porch were able to see that black fly subfossils stopped appearing in the mud at a depth that is consistent with the arrival of humans on each of the extirpated islands (subfossils are still present right up near the surface on Mangaia (medium blue), which is why the researchers think Simulium I. teruamanga is still alive but undetected there). On Atiu (light blue), the researchers report that the two streams which could conceivably contain black fly larvae are heavily disturbed by domestic pigs, and subfossils are only found deep in the mud of the swamps. On Raivavae, the area surrounding the subfossil-rich swamps is now taro farm, and the mud cores suggest the island had been heavily forested with strong streams up until humans arrived, when things change and black fly subfossils stopped showing up.

As humans spread across the globe and modify the land to suit our needs, it’s clear there are species which will pay the price for our expedited expansion. Black flies may be viewed as a pest in much of North America, but we should reconsider who is really having the bigger impact on the other. While it’s most likely too late for Simulium I. raivavaense, it may not be for other species being pushed towards the brink by human activity.

—–

CRAIG D.A. & PORCH N. (2013). Subfossils of extinct and extant species of Simuliidae (Diptera) from Austral and Cook Islands (Polynesia): anthropogenic extirpation of an aquatic insect?, Zootaxa, 3641 (4) 448. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3641.4.10